Why Are We Seeing Fewer Colors in Our Lives?

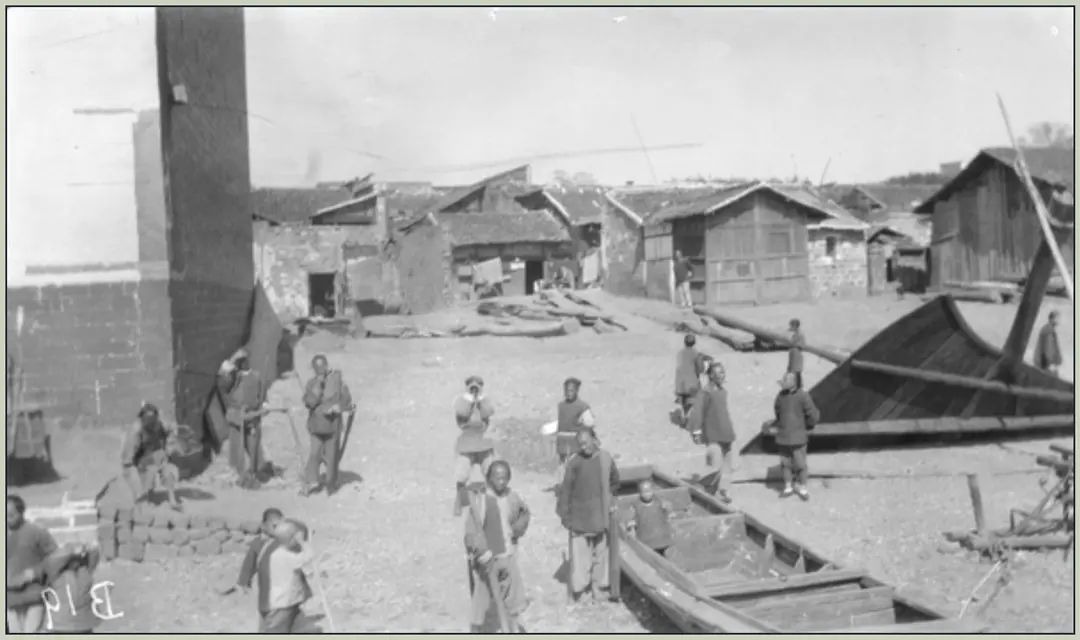

Lately, I’ve often found myself captivated by old photographs. I’ve been particularly drawn to the "Historical Photographs of China" project by the University of Bristol, which mostly features black-and-white images of Chinese streets, docks, teahouses, and farmhouses from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China. The people in these photos are dressed in simple clothes, the hillsides are bare, and the streets are dusty. By today’s standards, there’s almost no semblance of "quality of life." Yet, the more I look, the more I sense an indescribable feeling of stability in these images.

It’s a kind of decaying, orderly beauty. What is a road, what is a stall, where people should stand—everything is clearly defined. There are few colors, but the relationships are not chaotic.

Of course, I know it wasn’t exactly a stable era. Poverty was real, and the grayness was real. Yet, strangely, scrolling through these photos one by one brings a sense of calm. Unlike today’s images, which are eager to please or express an attitude, these photos simply present a world with a quiet, detached clarity.

It was only when I looked back at reality that I realized something had changed: the colors around us seem to be slowly fading away.

In underground parking lots, rows of cars are almost exclusively black, white, or gray. Occasionally, a dark blue one stands out as strikingly noticeable. Shopping malls, office buildings, and cafes share a highly uniform aesthetic—concrete-gray walls, cold white lighting, glass and metal surfaces gleaming with the same sheen. Even on our phone screens, app icons are becoming increasingly "standardized," as if color itself has become something to be restrained.

Even the way people dress follows this trend. Low saturation, no patterns, no logos—this is often described as "sophisticated," "timeless," or "safe." Bright colors, on the other hand, are easily seen as flashy, unsteady, or even somewhat inappropriate.

This isn’t because we’ve returned to an era of material scarcity. Quite the opposite—it’s because there’s too much of everything.

When choices become overwhelming, people begin to actively abandon differences. Black, white, and gray require no explanation; minimalist styles demand no judgment; a unified aesthetic reduces the risk of making mistakes. The fewer the colors, the safer it feels; the more one’s style resembles others’, the less likely they are to be noticed.

Slowly, color has shifted from a form of expression to a burden.

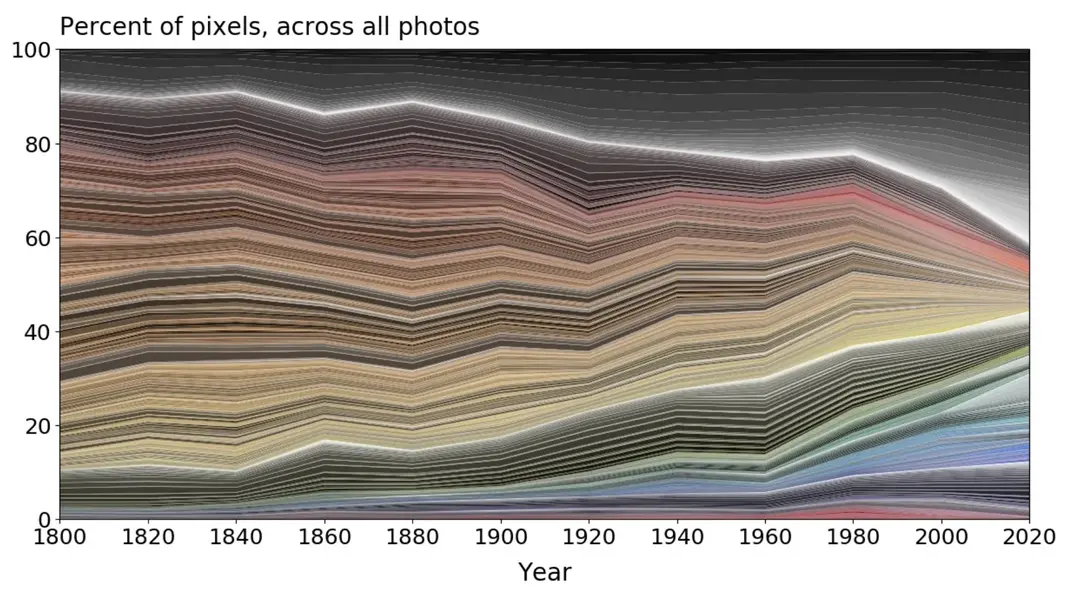

As research from the Science Museum in the UK shows, by analyzing the colors of 7,000 artifacts from the modern scientific era, it was discovered that humanity’s use of color has become increasingly conservative over the past century.

In such an environment, bright colors are no longer just an aesthetic choice but more like a statement. They signify a willingness to be seen and imply that one might have to bear extra attention and judgment for being "different." As a result, people begin to consciously tone themselves down, suppress their emotions, fold away their expressions, and blend into the background as much as possible. Over time, this personal-level restraint shapes the public environment in turn, and even spaces themselves gradually lose patience with color.

Those old photos from the late Qing Dynasty are entirely black and white, yet they don’t feel oppressive. Their monochrome is a result of the era’s limitations, while today’s "decolorization" feels more like an active collective choice. In an uncertain reality, people tighten up, minimizing risks.

The world, as a result, looks cleaner and quieter.

Walking through the city at night, the lights are still bright, but it’s hard to describe the scene as lively. It’s not that it isn’t prosperous, but rather that it lacks vibrancy. The muted colors are like stored-away emotions, quietly lying in corners—not making a fuss, yet always present.

Perhaps when people regain a bit more certainty about the future and a little more tolerance for differences, these colors will slowly return. Not in a noisy way, but like spring, naturally climbing back onto the streets, the corners of clothes, and people’s faces.

Until then, we’ll likely continue living in this restrained, austere landscape. It may seem orderly, but it occasionally makes us nostalgic for those less refined yet still vibrant days of the past.

References:

- University of Bristol Historical Photographs of China Project: hpcbristol.net

- Colour & Shape: Using Computer Vision to Explore the Science Museum Group Collection: lab.sciencemuseum.org.uk/colour-shape-using-computer-vision-to-explore-the-science-museum-c4b4f1cbd72c

#aesthetic changes #urban observations #daily life #social psychology #modernity