Why, After 18 Years in Guangdong, Do I Still Not Speak Cantonese?

On the way home from picking up my daughter from school yesterday, she asked me a soul-searching question: Why does our family speak Mandarin? Indeed, Old T's entire family hails from the same county in Hunan, but since moving to Guangdong, we've all naturally switched to Mandarin. Especially Lawtee himself—having been in Guangdong for 18 years, he's spoken Mandarin the entire time, which feels somewhat odd.

The Headache of Hunan Dialects

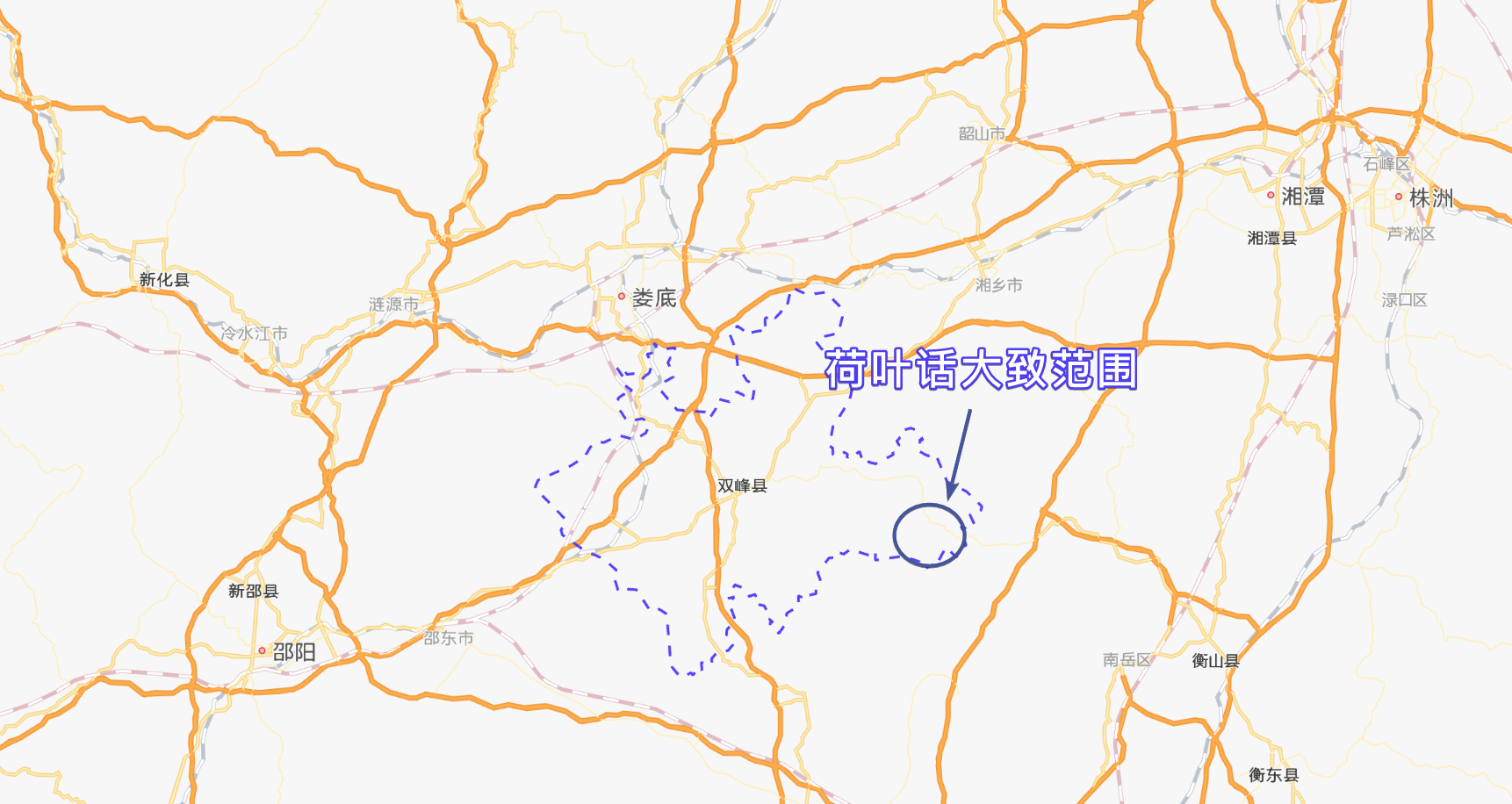

Lawtee reflected on his language learning journey. From childhood, his family only spoke one dialect, locally called "Tuhua Zi" (local vernacular). When Lawtee was about to start primary school, his parents, considering that the only teacher in the village school taught solely in this dialect, sent him to the central school in the township. It was there that Lawtee first encountered Mandarin and learned that "Tuhua Zi" had another name: "Heye Hua."

The origins of "Heye Hua" are lost to time, but Lawtee once read in Tang Haoming's Complete Works of Zeng Guofan that Zeng, despite living in Beijing for over a decade and learning some Beijing dialect, primarily spoke "Heye Hua" within his Hunan Army, switching to a northern-accented version for outsiders to ensure understanding. This indirectly shows that "Heye Hua" has been stably passed down for centuries. However, frankly, this dialect is confined to most of Heye Township; just a bit farther out, communication becomes difficult. Hence, when Zeng Guoquan, Zeng Guofan's brother, recruited soldiers, he insisted on using not only Hunan locals but specifically those from within a ten-mile radius of their home—roughly the widest reach of "Heye Hua."

By middle school, Lawtee noticed strange accents emerging on campus. The most typical example was his own name, pronounced differently by various people. For instance, the character "泽" was read as "jaak," "zeek," or "qiia" in different parts of our township. Such pronunciation variations often led to nicknames, casting a shadow over Old T's childhood.

At 15, Lawtee went to the county town for high school and was immediately bewildered stepping out of the bus station—what "bird language" were these people speaking? Not only couldn't he understand them, but they couldn't understand him either. Left with no choice, Lawtee resorted to the "plastic Mandarin" he'd learned in school to communicate, often met with puzzled looks: "Clearly a country bumpkin, yet speaking Mandarin?"

This clash between "country talk" and "county talk" made Lawtee frequently feel another form of "discrimination"—not the superiority of townsfolk over villagers, but the frustration from communication breakdowns: "A county local having to switch language channels for a villager."

Unable to beat them, Lawtee joined them. In this environment, he began learning "county talk" (often called "Yongfeng Hua" or, more stubbornly, "Shuangfeng Hua," named after the county, similar to how "Guangdong Hua" or "Cantonese" typically refers to "Guangzhou Baihua," ignoring other dialects in Guangdong). Back then, many students from other townships, like Old T, also started learning "Shuangfeng Hua" to avoid pointless internal friction in dialect clashes.

Even after years in the county town, Lawtee now recalls that his "Shuangfeng Hua" was barely understood by locals. He had taken a shortcut, learning only the intonation while retaining "Heye Hua" vocabulary. So, on recent visits to the county, he's avoided "showing off" and sticks to Mandarin.

After marriage, though both he and his wife are from the same county, her hometown dialect from another township made communication like "a chicken talking to a duck." They eventually defaulted to Mandarin, as did their parents when they visited. Now, when their kids visit their hometown, they can't understand either the "Heye Hua" from their dad's side or the "local talk" from their mom's side—the county dialect sounds like a foreign language to them.

Cantonese: Quite Different from Hunan Dialects

Eighteen years ago, Lawtee started university in Guangdong and encountered "Cantonese." After some exposure, he thought Cantonese wasn't much different from Hunan dialects—many everyday words were similar, just with different pronunciations and tones. So, he applied his high school experience learning "Shuangfeng Hua," treating Cantonese as another tonal variation and trying to translate his "Heye Hua" into Cantonese tones. The result was far off—awkward for him to speak and even more uncomfortable for others to hear.

Throughout this, Lawtee pondered: Is Cantonese really that different from Hunan dialects? Historically, Guangdong and Hunan are neighboring regions, both part of the Chu State since the Warring States period. During the Han and Tang dynasties, the route from Chang'an and Luoyang to Lingnan passed through Hunan (only shifting to Jiangxi after the Southern Song capital moved southeast). For example, Han Yu traveled to Guangdong five times via Chenzhou, leaving stories like "Wen Gong's Gallop" on the ancient Hunan-Guangdong path, where "boats stop at Chenzhou, horses die at Chenzhou." After the Five Dynasties, many Jiangxi migrants moved to Hunan and Guangdong; Old T's ancestors, for instance, relocated from Jiangxi to Xiangxiang in 924 AD, while many Guangdong genealogies trace back to Nanxiong Zhuji Lane, also via Jiangxi. Logically, the dialects of Hunan, Jiangxi, and Guangdong shouldn't differ drastically.

But Lawtee remembered another story: After Zeng Guoquan captured Tianjing, he captured Hong Renda, brother of Hong Xiuquan. Hong, having only farmed and knowing no official language, couldn't understand Zeng's "Xiangxiang official speech" and only spoke "Huaxian local talk." Zeng had to enlist "Song Wang" Chen Defeng as a translator. Chen wasn't even from Guangdong but from Guiping, Guangxi, yet he managed the task. This shows that, at least in the 19th century, a Hunan native trying to talk to a Guangdong native wasn't easy—a Guangxi translator was needed.

Thanks to Guangdong's openness and inclusiveness, Lawtee only briefly self-studied Cantonese in university, mostly using Mandarin with peers. This habit persisted into his career and remains today.

Why I Haven't Mastered Cantonese

To say Lawtee never seriously studied Cantonese would be unfair. He has 8-10 Cantonese learning books at home, read countless times, and in reality, he can understand various Baihua dialects from Guangfu, local dialects from western Guangdong, and even some Hakka-accented speech. But speaking it fluently and accurately is a struggle.

A key reason, as mentioned, is that when speaking Cantonese, Lawtee unconsciously draws on his experience learning "Shuangfeng Hua," naturally treating Cantonese as another dialect tone and ignoring its conventional expressions. For example, the simplest word "冇" (meaning "not have") exists in both Hunan and Guangdong, so Old T理所当然地 applies Hunan phrases like "冇事," "冇得," and "有冇" to Cantonese. Sentences like "有冇事我可以帮到你" (Is there nothing I can help you with?), "哩单野冇得搞手" (This matter has no solution), and "今日我冇空" (I'm not free today) leave listeners confused. While they might grasp the gist, it's far from authentic Cantonese.

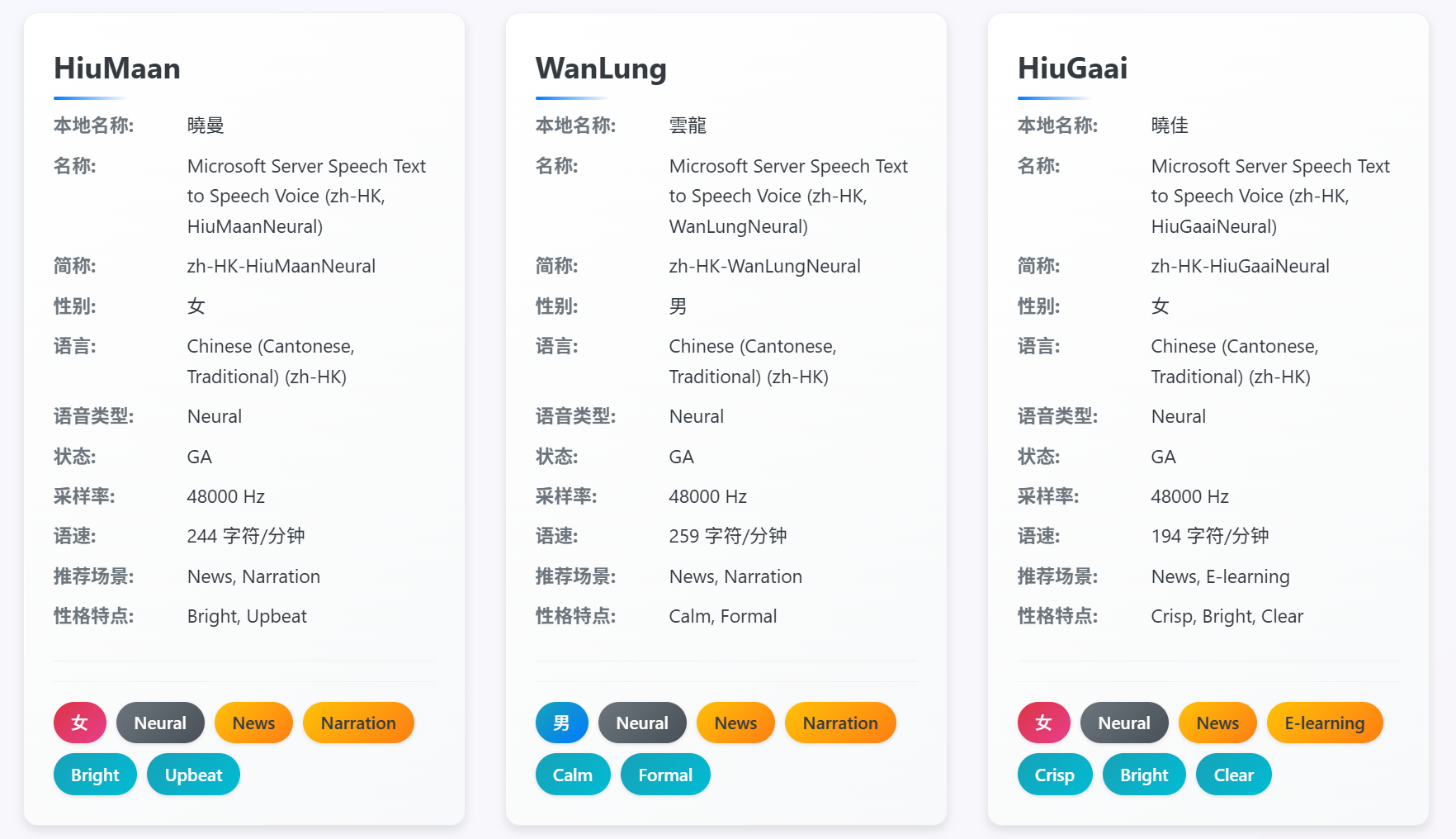

Another issue is mixing written and spoken language. For years, Lawtee worked in law, where Mandarin usually sufficed, and any Cantonese use involved reading written text aloud with Cantonese pronunciation. His legal training made him wary of miscommunication, so "reading as written" became a habit. This also ties to his early "crooked path" in learning Cantonese: while working in a remote town in the Pearl River Delta, he used text-to-speech (TTS) on his phone to self-study, listening to novels and books. Since TTS is based on written language, his ears and mouth grew accustomed to this style.

Additionally, when Lawtee encounters words he can't pronounce in Cantonese, he unconsciously switches to "Shuangfeng Hua" tones. It's like making a PPT with a nice font, only to find some characters missing and defaulting to "Fang Song" style. Worse, his "Shuangfeng Hua" is a "defective product"—not a real language skill but a vague "pronunciation impression." This substitution causes double distortion: it strays from the target (Cantonese), isn't the true source (written language), and isn't genuine Shuangfeng Hua.

What Lies Ahead

In recent years, when Lawtee visits his hometown, many people—supermarket cashiers, gas station attendants, shop owners—seem to be speaking Mandarin. Even when he switches to "Heye Hua," they often reply in Mandarin. This is especially true with younger relatives, almost all of whom now speak Mandarin.

On New Year's Day this year, Old T's tire picked up a large nail on the way back from Shaodong relatives to Heye. Far from home, he spotted a lit repair shop in Shuangfeng county town and decided to patch the tire. Worried about overcharging, especially with his Guangdong license plate, he had his wife—more fluent in "Shuangfeng Hua"—handle the talk. But, oh well, the owner spoke Mandarin the whole time, making Lawtee feel like he'd "measured the gentleman's heart with his own mean gauge."

Looking back, at 15, Lawtee relied on that "plastic Mandarin" to communicate with classmates across the county. Later, venturing to Guangdong and traveling nationwide, he still depended on that "plastic" foundation from his rural teachers. So, when his daughter asked, "Why does our family speak Mandarin?" Lawtee blurted out, "Because Mandarin is modern standard Chinese."

Over 2,300 years ago, King Wei of Chu, Xiong Shang, incorporated Lingnan into Chu territory, implementing "Chu systems." A century later, the Qin Dynasty unified China with "standardized tracks and writing." Subsequent dynasties promoted their own "official languages" to pave the way for smooth communication. In modern times, massive population movements have made a common language standard essential for 1.4 billion people. This standard language may not carry the rich flavor of local dialects, but it is the solid foundation for the smooth flow of daily life and social interactions.

#cantonese #xiang chinese #shuangfeng #hunan