How to Separate Trial and Execution

The Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee proposed many reform measures to improve the socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics. Among them, in the aspect of perfecting the mechanisms for fair law enforcement and justice, there are several key reform tasks, including the separation of trial and execution.

(35) Improve the mechanisms for fair law enforcement and justice. Improve the mechanisms where supervisory organs, public security organs, procuratorial organs, judicial organs, and judicial administrative organs each perform their duties, and where supervisory power, investigative power, prosecutorial power, judicial power, and execution power cooperate and constrain each other, ensuring that all links of law enforcement and justice operate under effective supervision and constraints. Deepen the reform of separating judicial power and execution power, improve the national execution system, and strengthen the supervision of execution activities by parties, procuratorial organs, and the public throughout the process. Improve the relief and protection system for law enforcement and justice, and improve the state compensation system. Deepen and standardize judicial openness, implement and improve the judicial responsibility system. Standardize the establishment of specialized courts. Deepen the reform of hierarchical jurisdiction, centralized jurisdiction, and extraterritorial jurisdiction of administrative cases. Build a collaborative and efficient police mechanism, promote the reform of local public security organs' institutional management, and continue to promote the reform of the management system of civil aviation public security organs and customs anti-smuggling departments. Standardize the management system of auxiliary police personnel. Adhere to the correct view of human rights, strengthen the judicial protection of human rights, improve the mechanisms for pre-review, in-process supervision, and post-correction, improve the system of compulsory measures involving citizens' personal rights and measures such as sealing, seizure, and freezing, and investigate and deal with crimes such as abuse of power for personal gain, illegal detention, and extortion of confessions through torture according to law. Promote full coverage of lawyer defense in criminal cases. Establish a system for sealing minor criminal records.

Compared to the statement in the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee in 2014, "promote the pilot reform of separating judicial power and execution power," the current proposal for the separation of trial and execution reform has a higher stance, more supporting measures, and heavier tasks.

The Concept of Separation of Trial and Execution

- Separation of Trial and Execution Work

Since 2000, the separation of trial and execution has been a key reform direction for courts. At that time, the separation was considered to be within the court, where judges were responsible for trials and execution officers were responsible for executions. The goal was to change the previous system where trial and execution were combined, and power was overly concentrated. In September 2000, the Supreme People's Court issued the "Notice on Reforming the Execution Institutions of People's Courts," proposing to "actively explore the separation of execution adjudication power and execution implementation power, with adjudicators and executors each responsible for their duties, cooperating and constraining each other."

- Separation of Judicial Power and Execution Power

Since 2014, the separation of trial and execution has entered a new exploratory phase. During this phase, some local courts have explored further separating the parts of execution work that involve the exercise of judicial power. This includes execution objection reviews, execution supervision, and third-party objection procedures, which are all handled by trial divisions, while execution departments focus solely on the execution of judgments.

- Judicial Power and Execution Power Handled by Different Institutions

In theory, there have long been calls for judicial power and execution power to be handled by different institutions. Currently, the execution power exercised by Chinese courts is essentially civil execution power, while criminal execution is already handled by prisons, detention centers, and community correction institutions. The latter process is more complex and the power is more dispersed, but overall, it is primarily handled by judicial administrative organs with the assistance of public security organs. There have been calls in theory for the civil execution power of courts to be transferred to judicial administrative organs or for a separate national civil execution organ to be established. However, since civil execution power is of great importance for maintaining judicial authority, transferring it from courts is much more difficult than transferring anti-corruption and anti-malfeasance functions from procuratorial organs. Previously, courts have largely avoided this issue when discussing the separation of trial and execution.

The Purpose of the Reform

Solving the Problem of Difficult Execution

Since the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee proposed "comprehensive deepening of reform," problem-oriented reform has become the most significant feature of reform. Major reforms must aim to solve major problems.

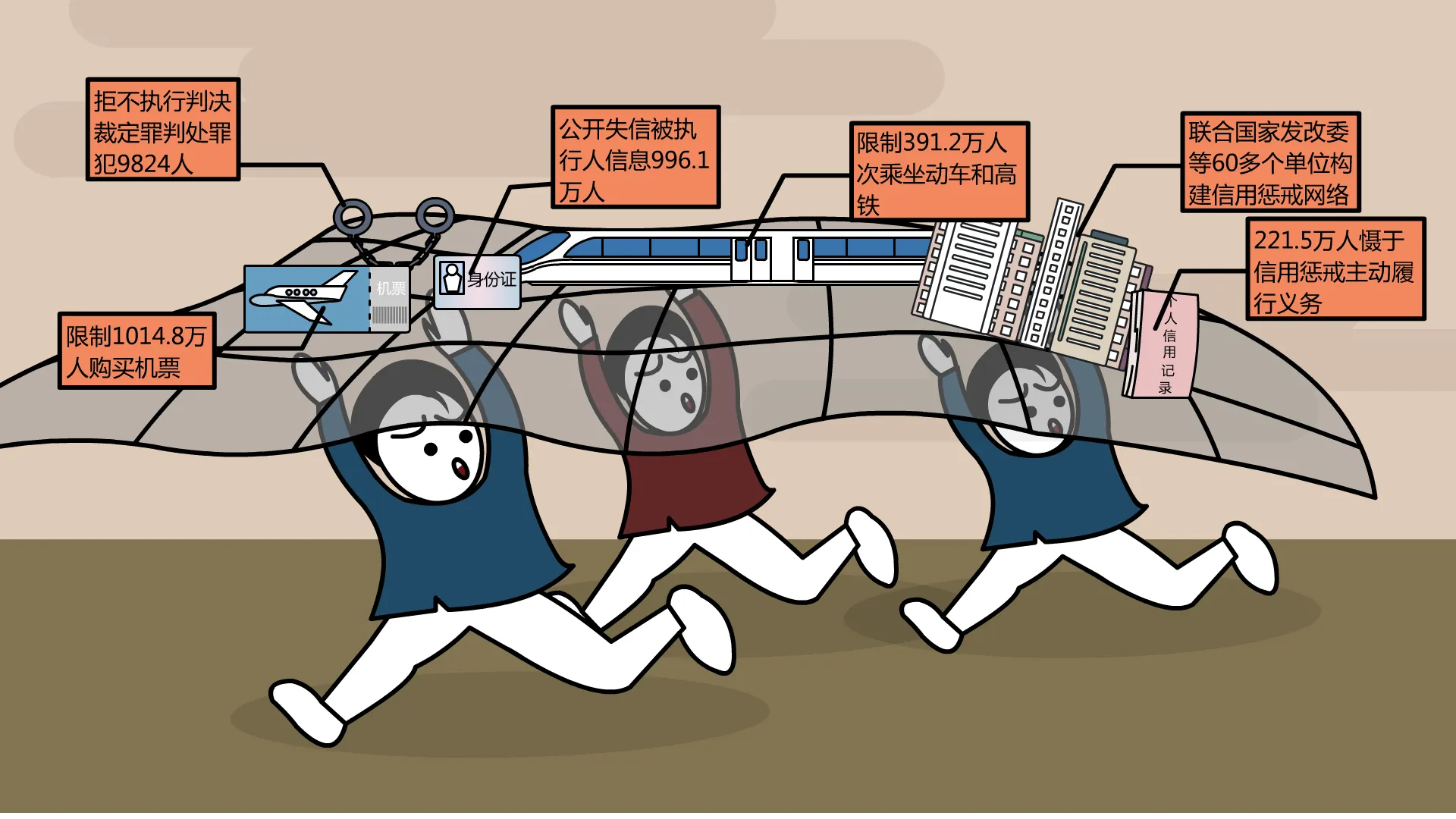

The major background for the separation of trial and execution reform proposed in 2014 was the problem of "difficult execution." The Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee proposed the goal of "effectively solving the problem of difficult execution," calling for the formulation of a compulsory execution law, standardization of judicial procedures for sealing, seizure, freezing, and handling of涉案财物, and acceleration of the establishment of a credit supervision, deterrence, and punishment legal system for失信被执行人, to ensure that winning parties can timely realize their rights.

Subsequently, the Supreme People's Court proposed to basically solve the problem of difficult execution within two to three years. It was after this that terms like "deadbeat" and "blacklist" became hot topics in society.

During this period, the execution work of courts basically brought together all relevant government departments to form a joint effort, including the establishment of mechanisms for联网查封, freezing, and扣押 of property such as houses, cars, deposits, stocks, and funds, as well as joint惩戒限制 mechanisms for air tickets, high-speed rail, hotels, and出入境. Most of the execution measures that could be thought of and done were done to the best of their ability.

Undoubtedly, after three years of攻坚 to "basically solve the problem of difficult execution" and many years of work to "effectively solve the problem of difficult execution," the overall problem of difficult execution has been fundamentally improved.

In summary, by 2024, the problem of "difficult execution" still exists to some extent, but given the current execution capabilities, it is unlikely to remain the primary goal for continuing to deepen the separation of trial and execution reform.

Improving the Supervision and Restraint Mechanisms for Law Enforcement and Justice

So, what is the driving force for continuing to deepen the separation of trial and execution? I think it is appropriate to look for answers in the reports of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee and the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee.

In the report of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee, the separation of trial and execution reform was proposed as part of optimizing the allocation of judicial functions, and measures to solve the problem of difficult execution were proposed as part of strengthening the judicial protection of human rights. In the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee, the separation of trial and execution reform was proposed as part of improving the mechanisms for fair law enforcement and justice. Comparatively, the current proposal for the separation of trial and execution has the core purpose of regulating the exercise of judicial power.

- Supervision and Restraint

The current report proposes to "improve the mechanisms where supervisory organs, public security organs, procuratorial organs, judicial organs, and judicial administrative organs each perform their duties, and where supervisory power, investigative power, prosecutorial power, judicial power, and execution power cooperate and constrain each other." Compared to the report of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee, supervisory organs and supervisory power have been added, and on the surface, there are still five organs and five powers, which might lead one to think that each organ corresponds to one power: supervisory organs - supervisory power, public security organs - investigative power, procuratorial organs - prosecutorial power, judicial organs - judicial power, and judicial administrative organs - execution power. However, in reality, supervisory, prosecutorial, and public security organs all have investigative power, and public security, judicial, and judicial administrative organs all have execution power. Perhaps the correspondence of five organs to five powers is a future reform direction, but for now, it is unlikely to be the case.

However, the civil execution work of courts clearly falls under execution power. In the context of the separation of trial and execution, the reform goal is to further build mechanisms for execution power to cooperate and constrain other powers.

- National Execution System

The national execution system is a new concept. Previously, there were concepts of the execution system and the criminal execution system. For example, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee proposed "unifying the criminal execution system," but in fact, the criminal execution system has not yet been fully unified, as the academic community has called for the transfer of public security detention centers to judicial administrative organs, which has not been achieved. The current proposal for a national execution system should be a higher-level concept than the previous execution system and criminal execution system. It should unify the concepts of civil execution and criminal execution. Under the new national execution system, civil execution and criminal execution should have closer coordination in their systems. The best solution would be for both to be exercised by the same department. Even if it is difficult to merge them immediately, they should be managed under a unified system; otherwise, this concept will lack vitality.

Personally, I believe that the construction of the national execution system could consider the separate management of execution bureaus at all levels of courts. For example, the execution bureau of the ×× Intermediate People's Court could be renamed the ×× Execution Bureau, co-located with the court or managed by the court.

- Execution Supervision

The current report proposes to strengthen the supervision of execution activities by parties, procuratorial organs, and the public throughout the process. This has always been a difficult point in execution work. In our daily work, we can feel that the supervision of courts by procuratorial organs has a gradual weakening process from criminal procedure supervision to civil trial supervision, administrative trial supervision, and execution supervision. In most places, procuratorial organs' supervision of courts' execution activities is almost ineffective. For parties, their supervision of execution activities is mainly reflected in the process of execution petitions. As for the supervision of execution activities by the public, it is even more difficult in practice.

Especially now that the court system is vigorously promoting "cross-execution" work. Although from the court's internal perspective, "cross-execution" can overcome local protectionism, effectively prevent interference from power, relationships, and personal connections, and curb the abuse of execution power and even execution corruption. However, for supervision work, "cross-execution" presents a major challenge for procuratorial organs. According to the current judicial system, procuratorial supervision of courts is based on jurisdiction, meaning that the execution cases handled by a county court should be supervised by the county procuratorate. However, for execution cases handled by a county court in other counties, it is questionable whether the county procuratorate still has the motivation to supervise. In fact, this has already been quite evident in administrative litigation supervision. In recent years, many places have implemented centralized jurisdiction for administrative cases. In such cases, not only do courts in the centralized jurisdiction areas not need to handle administrative cases, but the procuratorates in the same areas also almost no longer need to supervise administrative litigation cases. As for the procuratorates in the areas where centralized jurisdiction courts are located, they have little interest in supervising administrative cases that occur in other areas. The Third Plenary Session report proposes to "deepen the reform of hierarchical jurisdiction, centralized jurisdiction, and extraterritorial jurisdiction of administrative cases." In the reform process, local areas should pay attention to this issue.

The Future of the Separation of Trial and Execution Reform

Both the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee and the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee list execution power as a separate power, parallel to judicial power. This shows that the nature of execution power is clear: it is a separate power, not an appendage of judicial power.

Since the distinction has been made, a new question arises: does execution power still belong to the judicial category?

This is also a question worth studying. In the traditional legal context, law enforcement and justice belong to two different powers: administrative and judicial. Traditional "law enforcement" usually refers to administrative law enforcement within the scope of administrative law, while justice encompasses all stages centered on litigation. This includes public security investigation, prosecutorial prosecution, court trials, civil execution, and criminal execution, all of which are included in the judicial category.

However, in practice, the scope of justice has been continuously expanding, even extending to all public security organs, procuratorial organs, judicial organs, and judicial administrative organs. For example, the "Regulations on the Recording and Accountability of Internal Personnel Interfering in Cases in Judicial Organs" refers to internal personnel of judicial organs as personnel working in courts, procuratorates, public security organs, state security organs, and judicial administrative organs.

Based on this, the Third Plenary Session report presents two types of "law enforcement." One is still administrative law enforcement, and the other is law enforcement within the context of law enforcement and justice. This means that the activities of the above-mentioned supervisory commissions, courts, procuratorates, public security organs, state security organs, and judicial administrative organs are collectively referred to as law enforcement and justice. However, as to which of the five powers—supervisory power, investigative power, prosecutorial power, judicial power, and execution power—belongs to law enforcement and which belongs to justice, there is currently no conclusion.

The new concept of "law enforcement and justice" may be a concept that needs to be strengthened in the construction of the socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics. For example, in the "16-character policy" of "scientific legislation, strict law enforcement, impartial justice, and universal law-abiding," courts traditionally only emphasize "impartial justice." However, once execution power is considered as law enforcement within the context of law enforcement and justice, courts not only bear the responsibility of impartial justice but also the responsibility of strict law enforcement. In this case, the issue of the separation of trial and execution will become more prominent.

In fact, in my many years of work experience, party documents have long used both "law enforcement" and "law enforcement and justice." For example, in the "Regulations on the Work of the Communist Party of China in Political and Legal Affairs," there are expressions such as "law enforcement for the people," "law enforcement cases," "law enforcement supervision," as well as "law enforcement and justice work," "law enforcement and justice conditions," and "law enforcement and justice policies," all of which express the sum of law enforcement and justice. In addition, the Political and Legal Affairs Committee of the Party Committee also has a law enforcement supervision department responsible for supervising the exercise of power by political and legal units. The current expression of law enforcement and justice, I speculate, will further clarify the exercise of supervisory power, investigative power, prosecutorial power, judicial power, and execution power, and implement more precise supervision measures.

Personal Suggestions

Overall, the complete separation of trial and execution should be a major trend, but facing the deep water of reform, it is not something that can be achieved overnight. If separation must be done, I personally envision it could be done as follows:

- Establish a Compulsory Execution Administration Bureau under the provincial Department of Justice to oversee compulsory execution work in the province.

- Establish compulsory execution bureaus at the city and county levels, affiliated with the judicial bureau, primarily under vertical management but also accepting local leadership.

- Divert existing execution personnel in the court system, with some remaining in courts to supplement trial forces and alleviate the矛盾 of too many cases and too few people.

- Divert idle police forces in judicial administrative organs to compulsory execution bureaus to supplement compulsory execution forces.

- Convert execution judges to execution police, directly transferring existing positions and ranks to corresponding police positions and ranks to ensure待遇不降.

The main reason is that there are still many idle police forces in the judicial administrative system, especially in the戒毒 field. Previously, some members of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) have called attention to the fact that in some provinces, the ratio of戒毒 police to强戒 personnel has reached 6:1, and in many provinces and cities, police forces are even more idle.

At the beginning of 2023, Zhou Shihong, a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and the supervisor of the Anhui Lawyers Association, learned from the戒毒 management authorities of the Anhui judicial administrative department that the number of强制隔离戒毒 personnel in Anhui Province was less than 200, while the number of干部 and机构编制 in the强制隔离戒毒 management authorities and 8强制隔离戒毒场所 in the province was as high as 1240.

#law #courts #trial #execution #separation of trial and execution #third plenary session of the 20th central committee #fourth plenary session of the 18th central committee