Some Thoughts on School Phone Bans

This morning, as usual, Lao T opened his RSS reader and came across three consecutive news articles about mobile phone bans in primary and secondary schools. Surprisingly, they originated from different countries: the United States, France, and Singapore. It's strange—why does it suddenly seem like everyone is banning phones in schools?

What Are Other Countries Doing?

First, let's look at the United States. This RSS feed came from the HN homepage, a purely IT-focused forum that suddenly started discussing school phone bans.

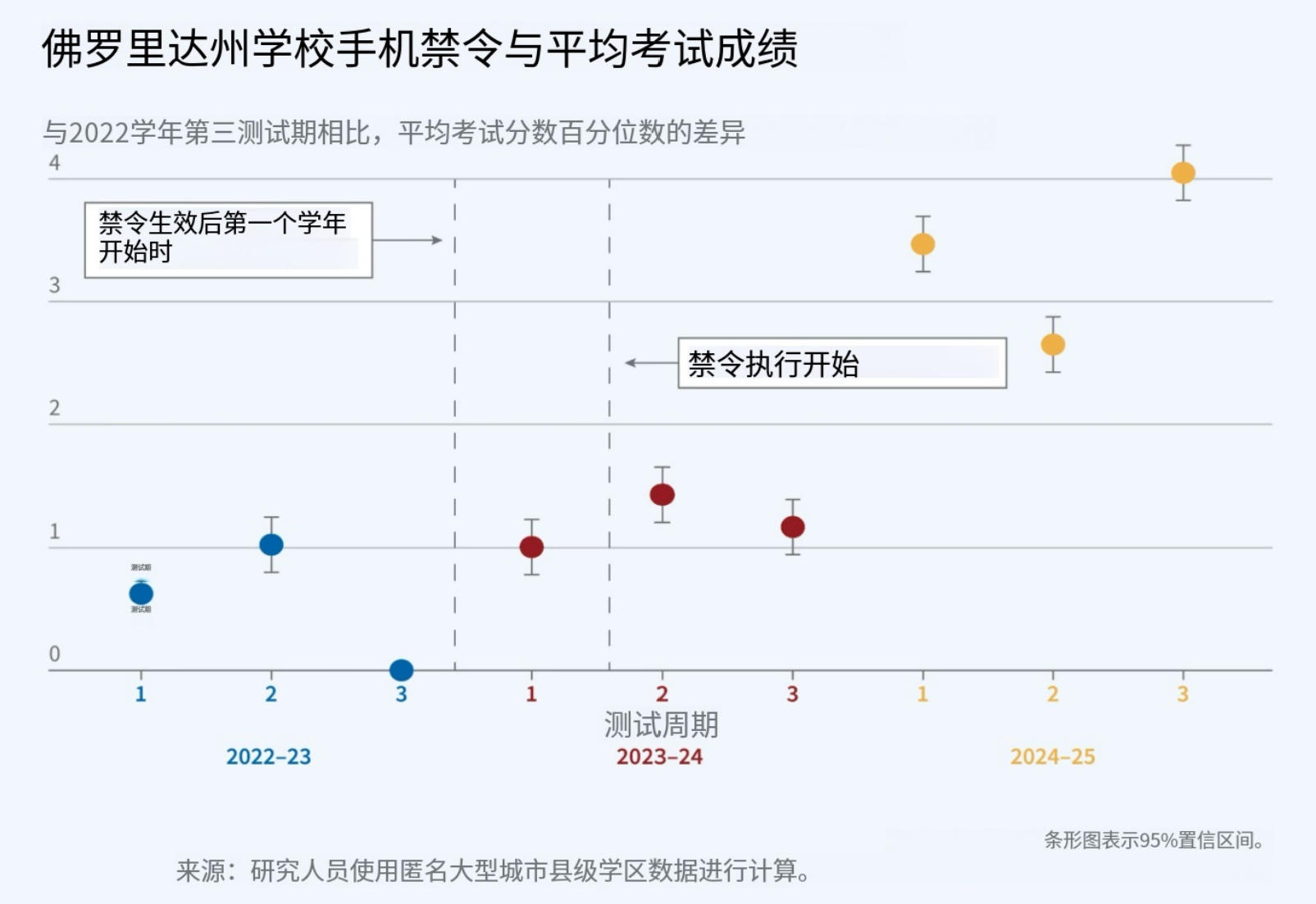

The article mentioned that a large urban school district in Florida began implementing a full-day phone ban in 2023. Unlike national bans that only prohibit phones in classrooms, this district requires students to keep their phones turned off and stored in their backpacks throughout the entire school day.

So, what were the results? According to a report from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), after two years of implementation, student performance improved, with average test scores increasing by 1.1 percentage points. Boys saw a 1.4-point increase, while middle and high school students improved by 1.3 points.

The data showed that phone usage in schools dropped by two-thirds, absenteeism decreased, and focus improved.

However, the path wasn't easy. The U.S. education system already faces numerous challenges, such as uneven resource distribution and social stratification.

When Lao T read the specifics, he was speechless. The article stated that as soon as the ban was introduced, disciplinary issues in schools increased significantly. In the first year, suspension rates rose by 25% and remained high throughout the year. Among Black male students in schools with high phone usage, suspension rates even increased by 30%.

It's a classic American response: "If the school bans phones, I'll just skip school."

In the first year of the policy's implementation, there was no change in student performance. It wasn't until the second year, when disciplinary issues stabilized, that academic improvements became noticeable.

Although the execution process was somewhat comical, it made Lao T realize that any reform requires time to adapt.

This isn't to say the U.S. approach is perfect, but their data-driven tracking offers valuable lessons that can help us avoid similar pitfalls.

Next, let's look at France and Singapore.

In France, President Macron announced that starting from the next academic year (2026–2027), the phone ban will be extended to high schools. Currently, France already bans phones in middle schools, requiring students aged 11 to 15 to keep their phones turned off and locked in lockers or special pouches. Now, the decision to extend the ban to high schools aims to reduce school violence, improve adolescent mental health, and address issues of loneliness among teenagers.

However, the French education system also has its complexities, such as long-standing disagreements between schools and parents. Still, this move demonstrates a commitment to addressing student concerns.

Drawing from France's experience, we might gain insights into balancing various stakeholders' interests when implementing such bans.

Singapore also recently introduced new regulations. On November 30, the Ministry of Education issued guidelines stating that starting in January 2026, secondary school students will be completely prohibited from using smartphones and smartwatches during school hours, including breaks, lunchtime, and extracurricular activities.

Since the reform and opening-up, we've learned many social governance practices from Singapore, such as community management and environmental sanitation.

This phone ban aligns with Singapore's consistent approach: strict measures with a focus on long-term effects, essentially equating to a ban on phones in schools.

Lao T believes that although these international approaches differ in context, they share a common core issue: phones are too distracting for children and need to be managed.

Domestic Policy Trends

Back in China, Lao T looked into it and found that in October of this year, the General Office of the Ministry of Education issued a notice titled "Ten Measures to Further Strengthen the Mental Health Work of Primary and Secondary School Students."

The fourth point of the notice specifically mentions cultivating healthy internet habits among students, requiring schools to "standardize the management of smart devices brought by students to school and strictly prohibit mobile phones and other electronic products from being brought into classrooms."

It also encourages students and parents to participate in a "screen-off action" to reduce excessive reliance on the internet.

This sounds quite practical, framing the "ban on phones in classrooms" as part of efforts to address mental health issues among primary and secondary school students. It tackles the problem at its source, preventing children from being influenced by algorithm-driven content that "sells anxiety."

However, upon closer inspection, this policy only bans phones in classrooms but doesn't prohibit them from being brought to school. This means students might still use them during breaks, lunchtime, or in dormitories.

This reminds me of some funny videos I saw on a short-video platform, where school administrators and students played "hide-and-seek," showcasing how phones were searched for in various "blind spots" in dormitories.

I checked the management methods at my two children's schools. They've long banned phones from being brought to school entirely. If students need to contact their parents, they can use public phones or borrow a phone from their homeroom teacher.

This shows that domestic management approaches vary significantly from school to school, with considerable autonomy. Stricter schools may have already implemented measures ahead of time.

Some Personal Suggestions

In October, when I attended a parent-teacher meeting at my daughter's school, what left the deepest impression was the homeroom teacher, who became emotional and tearfully shared her "frustrations" with us parents.

Just a month and a half into the semester, I found out that my daughter's homeroom teacher had changed again. During the summer break, I learned from the class group chat that her previous homeroom teacher had been promoted, and the school had hired a teacher from another top school in the city to take over. However, it was said that within less than a month, the new teacher resigned, forcing the school to ask the original teacher to return. The main reason was that many students in the class were somewhat "unruly" and didn't respect the new teacher's authority, leading to a noticeable decline in classroom order and academic performance within just a few weeks. Since the school currently ranks first in the district in terms of academic advancement and exam results, all teachers are working extremely hard, often from 7 a.m. to midnight, to maintain this hard-earned achievement. During our communication, the current homeroom teacher choked up several times, expressing deep disappointment over the recent issues in the class.

During that parent-teacher meeting, the homeroom teacher emphasized that students' addiction to short-video apps was a major factor contributing to their lack of focus in class.

It's not hard to understand. Short videos, with their "quick and easy" content, deliver sensory stimulation in just a few seconds, making even adults "unable to resist," let alone children.

Parents can't constantly monitor what their children are doing on their phones. What they're watching, whether it's healthy or not, often remains a "mystery."

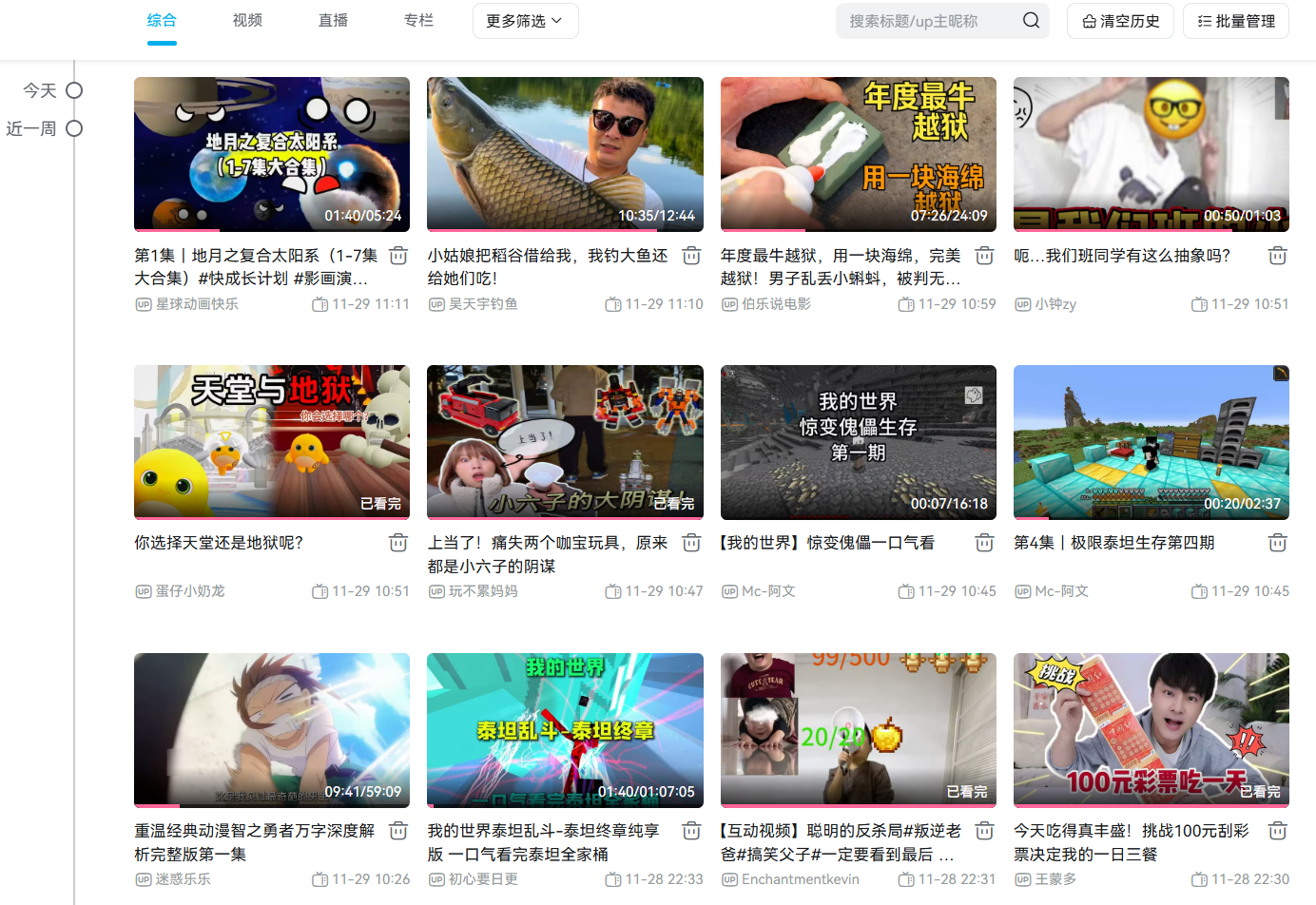

A few years ago, my family experienced something similar. My daughter enjoyed watching a certain bullet-comment video app on TV, so I specifically set up "child mode" to restrict the app to children's content.

Unexpectedly, one day she suddenly became emotional, saying that her parents were biased, favoring her younger brother and not caring about her.

At first, I didn't pay much attention until one day, when I happened to see her watching TV, I realized that the cartoons she was watching were actually teaching children about "scheming and deception" from the adult world.

I had no choice but to open the video app's playback history, scan through it, identify which accounts were posting such content, and "block" them one by one.

But honestly, this approach isn't very effective. It might work occasionally on "long-video" platforms, where the daily viewing volume isn't too high. However, on "short-video" platforms, the sheer volume of content makes it impossible to remedy the situation afterward.

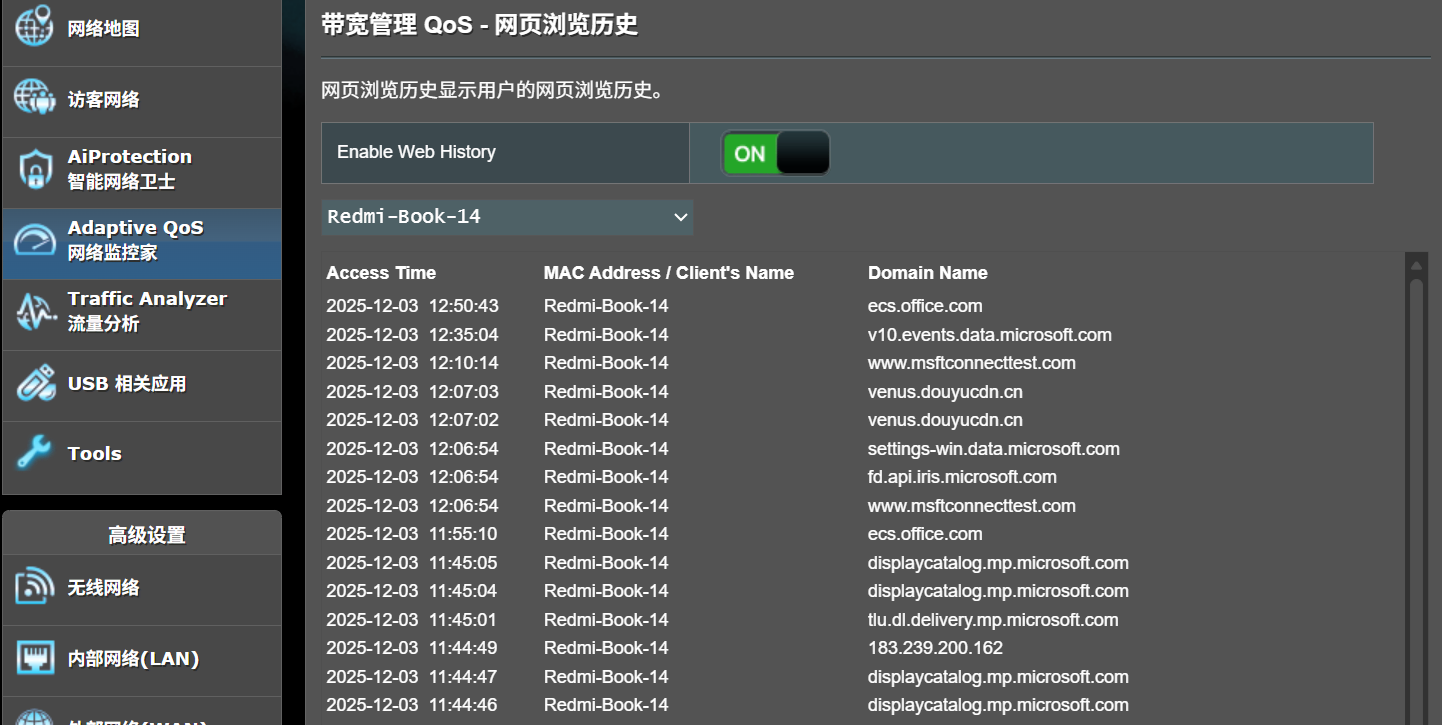

Most of the time, I resort to mechanical methods. For example, setting "healthy usage time" with a password on the phone or cutting off the TV's internet connection via the router. But these are the crudest forms of management. In terms of "content," I can only rely on the "conscience" and "algorithms" of each video platform to control what children can and cannot watch.

Fortunately, children nowadays are accustomed to independent apps, so we don't need to "outsmart" them in browsers as we did in the past.

I've digressed a bit. Returning to the topic of school phone bans, as a parent, I believe we should be more resolute and extend the ban to the entire school day.

First, it would allow children to truly disconnect from the internet for a while and engage in more face-to-face interactions. Second, it would reduce interference from exaggerated online content and protect their mental health. Third, in the long run, it could improve focus and academic performance. Of course, this shouldn't be implemented overnight. It needs to be rolled out gradually to avoid significant initial resistance, like the increased disciplinary issues seen in the U.S. during the first year.

Additionally, from a health perspective, excessive screen time can affect eyesight and sleep quality. According to some studies, teenagers who spend more than two hours a day on screens are more likely to experience worsening myopia or difficulty falling asleep. School phone bans could indirectly encourage children to engage in more physical activity, reading, and cultivating well-rounded hobbies.

Of course, practical considerations must be taken into account when implementing such bans. Schools need to provide emergency contact methods, such as landline phones or smart wristbands (without internet access). Parents should cooperate and build consensus so children don't feel unfairly treated.

At the societal level, platforms should optimize their algorithms to reduce the promotion of low-quality content. Ultimately, this isn't about control for the sake of control but about helping children develop self-discipline so they can better adapt to the digital age as they grow up.

Education is a gradual process, requiring patience and meticulous effort—a logic fundamentally at odds with the rapid iteration of content in the mobile phone era.

Education is a gradual process, requiring patience and meticulous effort—a logic fundamentally at odds with the rapid iteration of content in the mobile phone era.

There's no need to worry that children will fall behind the times if they don't use phones. In fact, looking back, how much of the C language or even older machine languages we once studied diligently are still in use today?

The tide of technology surges forward, and old tools will eventually fade from view. But amidst all the changes, the importance of foundational education remains paramount.

Without a solid foundation, everything crumbles.

Mastering the core knowledge and skills taught in school is the most reliable foundation for children to understand new things and adapt to societal progress in the future.

I also hope these policies can be effectively implemented, allowing more children to grow up healthily.

#school management #phone ban #mental health #international education