What It's Like to Work on a Factory Assembly Line

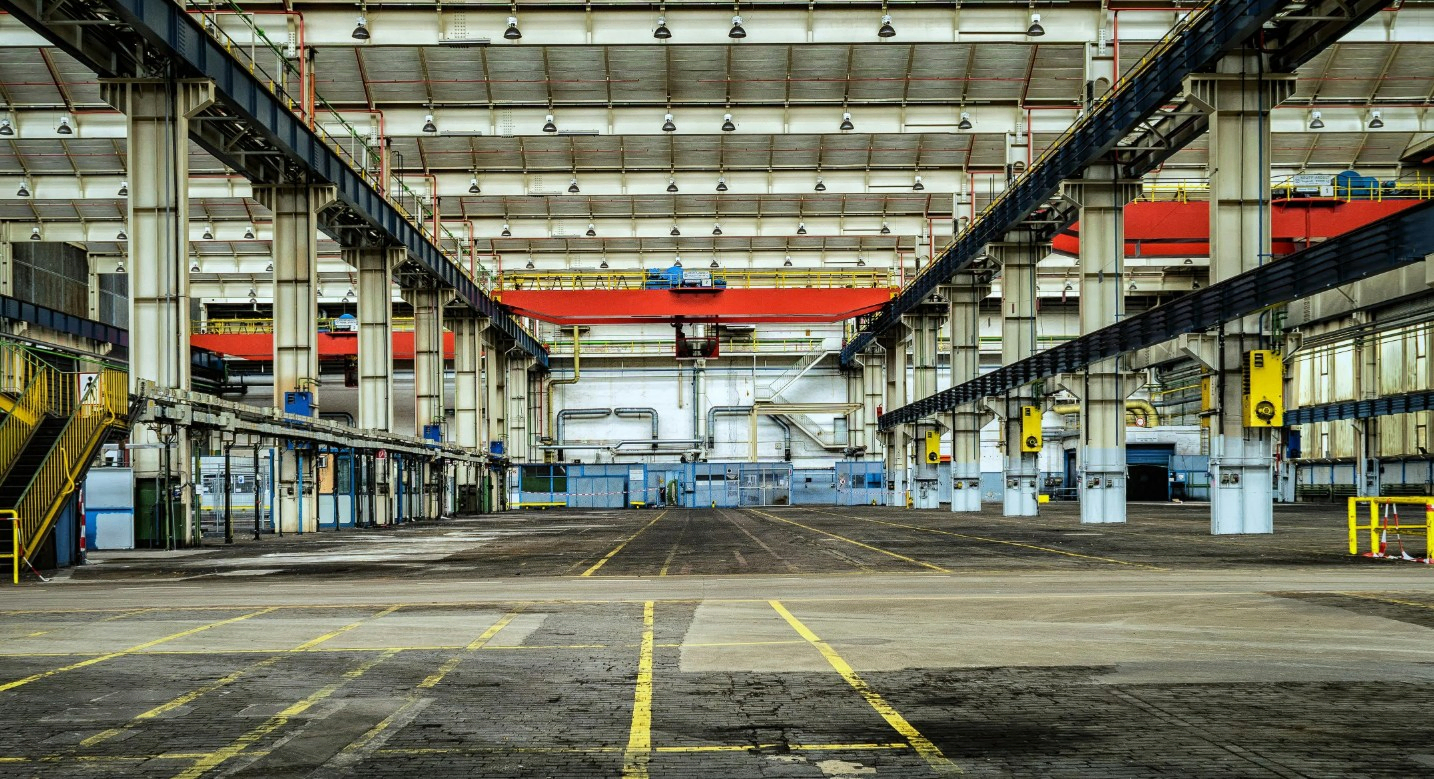

Recently, at the invitation of my daughter’s classmate’s parents, I had the opportunity to visit three small and medium-sized enterprises—two in traditional manufacturing and one in new materials. Unlike previous corporate visits confined to meeting rooms and office buildings, this time I explored every corner of the factory floors, gaining a clearer and more direct understanding of China’s most common production and manufacturing processes.

I often watch videos of domestic factory assembly lines on video platforms, amazed by the sensory impact of mechanized and intelligent production lines transforming simple raw materials into intricate and refined products.

But while watching, I couldn’t help but wonder: What is it really like for the workers involved?

Firsthand Impressions

When people think of assembly line factories, terms like “996” and “beasts of burden” often come to mind. However, the vast manufacturing sector is far too complex to be summed up by such negative stereotypes.

The three companies I visited were relatively small, each employing around 200–300 people. One produces daily chemical products, another organic materials, and the third packaging materials. To avoid unnecessary complications, I’ll refer to them as Companies A, B, and C.

Work Environment

Based on what I observed, all three companies seem to be among the better representatives in their respective industries. Yet, the most striking aspect of their production lines was the significant noise issue, especially at Company C.

Company A’s main workshop houses PET injection molding machines, each operated by one worker, producing bottles, caps, and plastic parts for daily chemical products. This area is the most densely populated and the noisiest. In contrast, processes like mold production, raw material preparation, filling, and final packaging were relatively manageable. For instance, the filling process is fully automated, with workers simply monitoring computer panels in an adjacent room.

Company B’s primary workshop features large mixing and processing machines for organic materials, all of which generate considerable noise. However, since most equipment operates automatically in enclosed systems, workers mainly monitor operations and perform minor external adjustments, making the noise somewhat tolerable.

Company C had the poorest working conditions of the three, largely because its raw material is paper. Much like office printers, which are often noisy, the factory’s large printers, cutters, feeders, and exhaust fans are all major sources of sound. Walking through the factory, it was nearly impossible to hear anyone speaking. The manager admitted that the noise levels exceed national standards.

Among the three, only Company C lacked air conditioning on the production line, reportedly because paper is sensitive to humidity, and AC could disrupt production. During my visit, the temperature was around 20°C, but the combination of high noise and the dry, paper-dust-filled air was still uncomfortable. I can only imagine how grueling it must be for workers in Guangdong’s summer heat of over 30°C. With orders consistently high, the company operates 24/7, meaning all workers rotate between day and night shifts. Perhaps the slightly cooler nights are the only perk of the night shift.

Working Hours and Compensation

Working hours varied across the three companies. Company A has only a day shift—12 hours from 8 AM to 8 PM, with just two days off per month, even less than the notorious “996” schedule. Company B essentially follows a 996 model: 12-hour day shifts with one day off per week. Company C has two shift patterns: 12-hour day/night shifts or 8-hour rotating shifts, with four days off monthly. Since the production line runs nonstop, those on 8-hour shifts get almost no breaks beyond occasional bathroom trips.

Hearing about Company A’s hours was disheartening. I thought 996 was tough, but this was worse. At the end of the production line, I saw seven or eight workers per line performing final packaging tasks. As long as the conveyor belt moved, they couldn’t stop, repeating the same motions tens of thousands of times daily. These individuals are someone’s cherished children, parents, or family pillars, yet their jobs leave little time for loved ones. Pursuing personal interests or simply getting out and about during off-hours seems nearly impossible.

Imagine being a packer at Company A: standing all day, eyes fixed on bottles moving along the conveyor, hands constantly loading boxes. Any slowdown halts the entire line. After 12 hours, you’re too exhausted to help with homework or handle family emergencies, and taking time off is difficult. Company B’s conditions might be slightly better, but staring at mixer screens with only one day off weekly leads to eye strain and mental fatigue over time. Company C’s shift rotations—coupled with night shifts and high noise—pose serious physical challenges.

In terms of pay, all three companies base contracts on the local minimum wage, with overtime bringing total monthly earnings to between 6,000 and 8,000 yuan. This barely matches the local average annual wage for urban private-sector employees, covering only basic living expenses. After deductions for social security and housing funds, take-home pay likely just covers rent, food, and children’s education, leaving little for savings. Unsurprisingly, many young people prefer gigs like food delivery or ride-sharing, which offer flexibility and potentially higher income, despite their own hardships.

Some Reflections

During the visits, each company’s manager shared their “hardship stories.” For example, the owner of Company A explained that he initially focused on cosmetic packaging—plastic bottles—but clients would haggle over fractions of a cent. Losing a bid by just one cent meant losing the customer. A few years ago, he had no choice but to take loans, expand operations to include raw material preparation, filling, and packaging, and shift to an OEM model producing finished goods to eke out a slight profit margin. He doubts this approach will keep him ahead for long, expecting competitors to follow suit soon. Company C mentioned that their major clients are Fortune 500 companies, which often forgo building their own warehouses and demand just-in-time deliveries. For instance, if a client requires 10 tons of materials by 10:05 AM, Company C must deliver to the exact factory spot between 9:35 and 10:05 AM. This imposes extreme logistics demands, with contracts disregarding weather or traffic delays; any lapse incurs heavy penalties. Consequently, they had to rent expensive warehouses near client factories and purchase a fleet of trucks to meet these demands.

These accounts were sobering. Essentially, the intense competitive pressures faced by business owners inevitably trickle down to employees, compounding the physical toll of the job with underlying stress about the company’s survival. The constant noise, repetition, and long hours are the norm on assembly lines—realities often overlooked by outsiders.

We who’ve had more education are fortunate; our office complaints pale in comparison. The assembly line experience is like an endless battle—no flexibility, no mental stimulation, just mechanical repetition and physical drain. This is the stark reality of manufacturing: behind efficient production lies the perseverance and sacrifice of countless ordinary people.

That said, it’s undeniable that manufacturing is undergoing transformation and upgrading. More companies are adopting automation and smart systems. For instance, after upgrading its production line, Company A automated many filling tasks, shifting workers to monitoring roles. This may reduce physical strain, but staring at data screens all day still causes eye fatigue and requires intense concentration. If Company B’s large mixers become AI-driven, operators might transition to remote debugging, potentially shortening hours but demanding new skills. For Company C, installing smart noise reduction and climate control could alleviate the stifling summer heat and aid recovery between shifts. However, upgrades bring concerns: as robots replace roles, low-skilled workers risk unemployment, and transitioning to fields like delivery or services offers unstable income with low barriers to entry. In short, from the assembly line perspective, upgrading is a double-edged sword—it lessens the “beast of burden” aspect but demands adaptability, lest workers be left behind.

This visit deepened my appreciation for the grassroots workers who are the backbone of “Made in China.” At the same time, I hope automation and smart upgrades will improve their working conditions, making assembly lines less grueling. If you have the chance, I encourage you to visit a factory yourself—the impact far surpasses anything described in writing or seen in videos.

#made in china #visiting factory assembly lines #manufacturing