Has the AI Inflection Point Arrived for the Legal Industry?

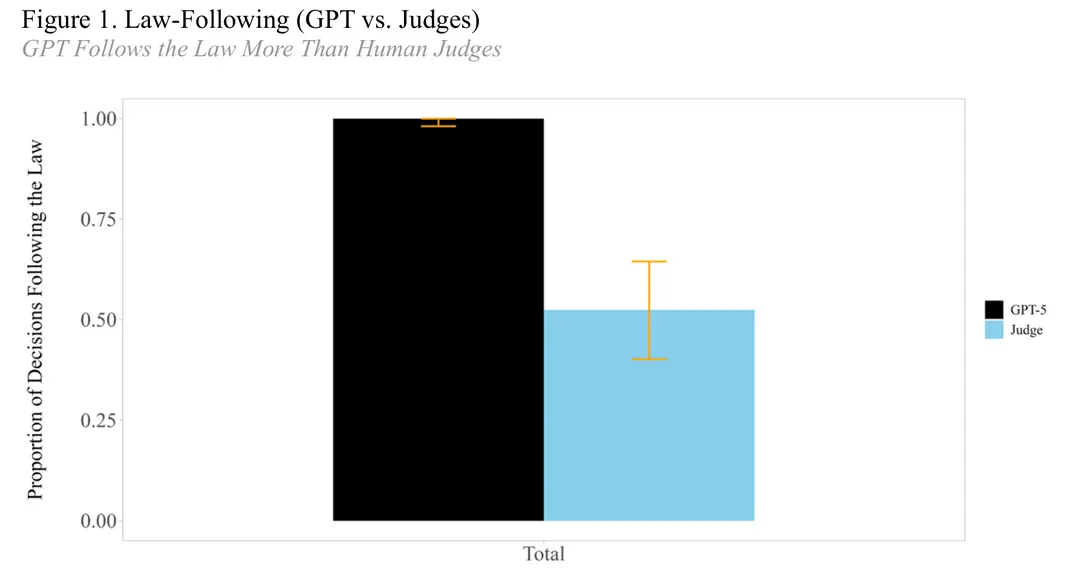

Recently, a paper from the University of Chicago Law School has caused a stir in legal circles. Authors Eric A. Posner and Shivam Saran published a paper titled “Silicon Formalism: Rules, Standards, and Judge AI” . The paper centers on a case where a friend offering a ride causes personal injury to the passenger due to a traffic accident. By switching variables such as rules versus standards, the level of sympathy for the parties, and the location of the accident, the study compares the legal judgments of GPT-5 with those of 61 U.S. federal judges. Ultimately, GPT-5 achieved a 100% accuracy rate in the experiment, while the overall accuracy rate of the 61 judges was only 52%.

When a language model demonstrates "zero errors" in a formal reasoning experiment, it is no longer just a technical metric but a signal at the institutional level.

Even more intriguing is that the release of this paper coincided almost exactly with the one-year anniversary of DeepSeek's launch of its reasoning AI, DeepSeek R1. That moment could almost be seen as the "inflection point" when various industries in China began to seriously acknowledge AI's reasoning capabilities. A year later, the technological curve has proven far steeper than most anticipated. Even legal professionals who were once highly skeptical of AI now have to face reality.

A widely circulated saying may not be an exaggeration: AI will not replace lawyers, but lawyers who use AI are replacing those who do not.

Silicon Formalism

The title of this article, "Silicon Formalism," is a direct translation of "硅基形式主义." However, the term "formalism" here is not the negative connotation of "going through the motions" as in Chinese colloquial usage. Instead, it refers to the jurisprudential sense of prioritizing rules and structured reasoning, akin to "rule-based jurisprudence" or Max Weber's "formal rationality."

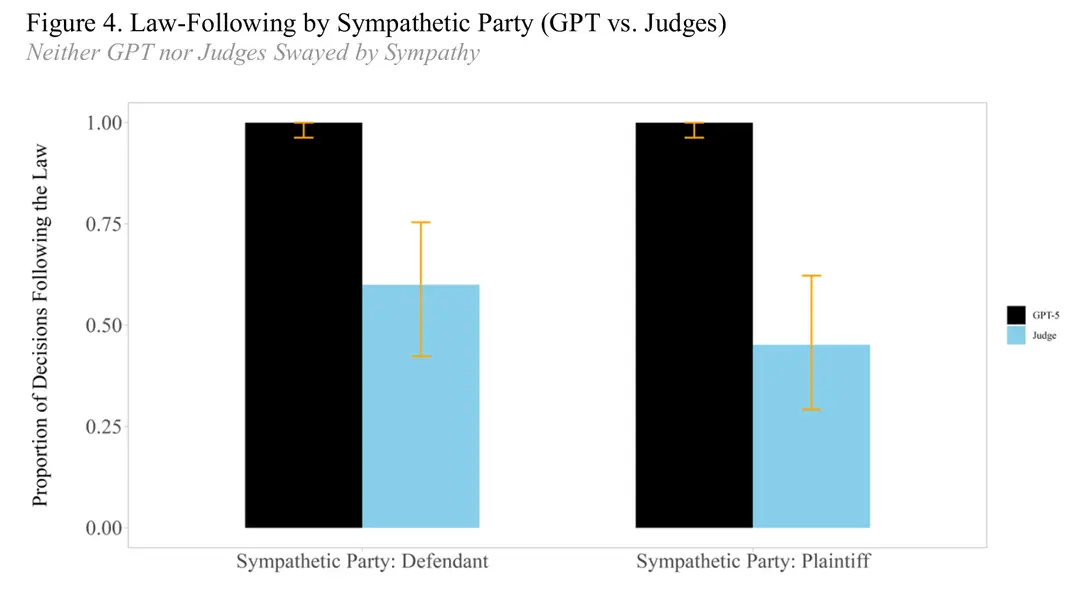

What truly deserves repeated reflection in this paper is not that "GPT-5 is smarter," but that it is more consistent. The experiment itself is not overly complex: switching between rules and standards, enhancing or diminishing the sympathy for the parties in the narrative, and creating differences in legal consequences under different state laws. Human judges, influenced by these variables, are swayed by contextual factors, while the model strictly derives conclusions based on the rule structure.

What does this mean? It means that in scenarios with clear rules, machines are closer to the "ideal formalist judge" than humans. They do not deviate due to sympathy, alter their application path due to narrative techniques, or emotionally stretch standard clauses. We have always said that law is not about 0s and 1s. Conflicts in evidence, value trade-offs, and situational judgments inherently introduce shades of gray into legal practice. But when a model demonstrates zero errors at the level of rule application, we must reconsider whether, in a significant proportion of cases, the law can indeed be highly formalized.

If the answer is "partially yes," then so-called "silicon formalism" is not merely a technological phenomenon but an institutional issue. Are the "errors" of human judges a necessary flexibility of the system or a manifestation of human cognitive limitations? When machines eliminate errors, are we losing human touch or approaching the rules themselves?

Where Is the Real Inflection Point?

The inflection point for AI in the legal industry does not lie in whether models possess astonishing capabilities, but in whether they have begun to alter the actual structure of legal production.

1. Document and Research Level: The Inflection Point Has Already Occurred

In scenarios such as contract review, clause comparison, due diligence summaries, and case summarization, large language models have already entered the actual production workflow. Legal tech companies like Harvey AI, which provide customized systems for law firms based on the GPT series of models, have been formally deployed and are being paid for by numerous top law firms globally. Harvey AI's valuation has reached $11 billion. Lawyers use AI within internal systems for contract analysis, legal research, and drafting initial versions of documents, establishing corresponding usage norms and risk control processes. This is no longer an experimental "toy" but a production tool operating within frameworks of billing, compliance, and internal controls.

Changes in corporate legal departments are equally evident. An increasing number of companies are embedding AI models into their internal knowledge bases for quickly retrieving compliance clauses, summarizing regulatory changes, and generating risk alerts. The starting point for legal text production is shifting from "manual drafting" to "machine-generated draft + human revision." The inflection point at this level has, in fact, already occurred.

2. Legal Reasoning Level: The Inflection Point Is Approaching

The zero-error results demonstrated in the paper indicate that in scenarios with clear rules and disputes focused on legal application, models can achieve consistency that matches or even exceeds average human judgment. If this capability proves consistently stable across different types of cases, then the handling logic for some cases will be reshaped. The value of lawyers and judges will increasingly lie in fact construction, evidence examination, and value judgment, rather than mere rule matching.

Of course, this does not mean AI will directly replace legal professionals. Instead, it signifies a shift in the professional structure. When rule application capabilities can be highly standardized, the hierarchy of skills within the legal profession will change. Those who are better at leveraging models to improve efficiency will gain a competitive edge.

3. Institutional and Power Level: The Inflection Point Has Not Yet Arrived

Admittedly, law is not merely about rule application. How issues are framed, how cases are narrated, and how standards are defined still remain in human hands. Models can only reason within given frameworks; they cannot determine the frameworks themselves. The legitimacy of judicial authority does not stem solely from reasoning accuracy but from procedure, credibility, and accountability mechanisms.

Currently, whether in the United States or China, models have not entered the formal structure of adjudicative power. They influence production processes, not power allocation. A true institutional inflection point must involve shifts in responsibility attribution and decision-making authority, and this has not yet happened.

From Hallucination Anxiety to Capability Stratification

A year ago, our concerns centered on AI hallucinations, erroneous citations of legal provisions, and model confusion in the face of complex evidence. Today, the direction of anxiety is shifting. We are beginning to discuss whether AI is more stable, less influenced by emotions, and more consistent than humans in certain domains.

The legal system has long oscillated between rules and standards. Rules provide certainty; standards provide flexibility. The "errors" of human judges and lawyers are sometimes the very source of discretionary space. The advantage of models lies precisely in eliminating errors. When rules are clear, they do not get fatigued, distracted, or swayed by narratives.

Therefore, the so-called inflection point is not about whether AI will replace judges or lawyers. In the short term, this scenario is highly unlikely. What is truly changing is the capability structure. When rule application, research summarization, and initial document drafting can be handled by models, legal professionals' time and value will increasingly shift toward fact organization, strategy design, and value judgment. Those who still spend time on automatable tasks will gradually lose their competitive advantage.

Perhaps the inflection point has already arrived. But what it changes is not the number of positions but the boundaries of efficiency and the stratification of capabilities. We have moved from "can it do it?" to "does it do it more consistently?" This, in itself, is a sign of the times.

#legal tech #artificial intelligence #large language models #legal reasoning #gpt-5 #deepseek