How Do Foreigners Choose Names When They Come to China

Recently, I came across an interesting article on Slate titled How the Government Ate My Name by an author named Giovanni Garcia-Fenech. Coincidentally, Lawtee had previously written a brief analysis titled What Impact Will the K Visa Implemented on October 1 Have on Ordinary People? , discussing potential foreign immigration trends. This got me thinking: do foreigners coming to China also face the issue of their names being “eaten”?

How the Government Ate My Name

The author of How the Government Ate My Name was born in Mexico with the full name Leonel Giovanni García Fenech, which follows the standard naming convention in Spanish-speaking countries, reflecting family heritage and cultural history.

However, after immigrating to the United States, his name was simplified by the U.S. bureaucracy. During naturalization, one of his names was dropped, and his driver’s license and passport displayed his names in a confusing order, even abbreviating it to “Giovanni F. Garcia.”

When the author later moved from the U.S. to Spain, he faced difficulties obtaining a Mexican passport due to name mismatches in his documents. He humorously described these experiences, emphasizing the fragility of names as carriers of identity and the inconveniences caused by name changes across different countries.

What surprised Lawtee the most was a small anecdote mentioned at the end of the article:

The author encountered an elderly Chinese shopkeeper in Spain whose name was “Lola.” The origin of this name was simply that a young girl named “Lola” had previously worked in the shop. Customers would frequently come in asking, “Where is Lola?” Over time, through these repeated inquiries, the Chinese shopkeeper became known as “Lola.”

Situations in Other Countries

The issue in the United States primarily stems from an English-language environment that does not support characters outside the ASCII set (English letters and punctuation), leading to replacements of letters like ü, ä, and ß. There is also cultural resistance to long names; even names with three words are often awkwardly shortened or abbreviated. For example, Obama’s full name Barack Hussein Obama is usually written as Barack Obama or abbreviated to Barack H. Obama.

However, after researching online, Lawtee found that this kind of “identity friction” caused by names clashing with bureaucratic systems is not unique to the United States; it happens all over the world.

For instance, a common issue is with Russian surnames, which often include gender-specific suffixes (e.g., male -ov, female -ova, as in Ivanov or Sharapova). When immigrating to English-speaking countries, these surnames are often forcibly standardized to the male form, resulting in mismatches between the name on documents and the individual’s actual gender.

Some Slavic countries also face challenges when transliterating English names into Cyrillic, leading to awkward or “neither-here-nor-there” results due to a lack of corresponding characters.

In France, the government often encourages immigrants to adapt to local naming conventions to promote cultural integration, viewing the adoption of French names as part of the “assimilation” process.

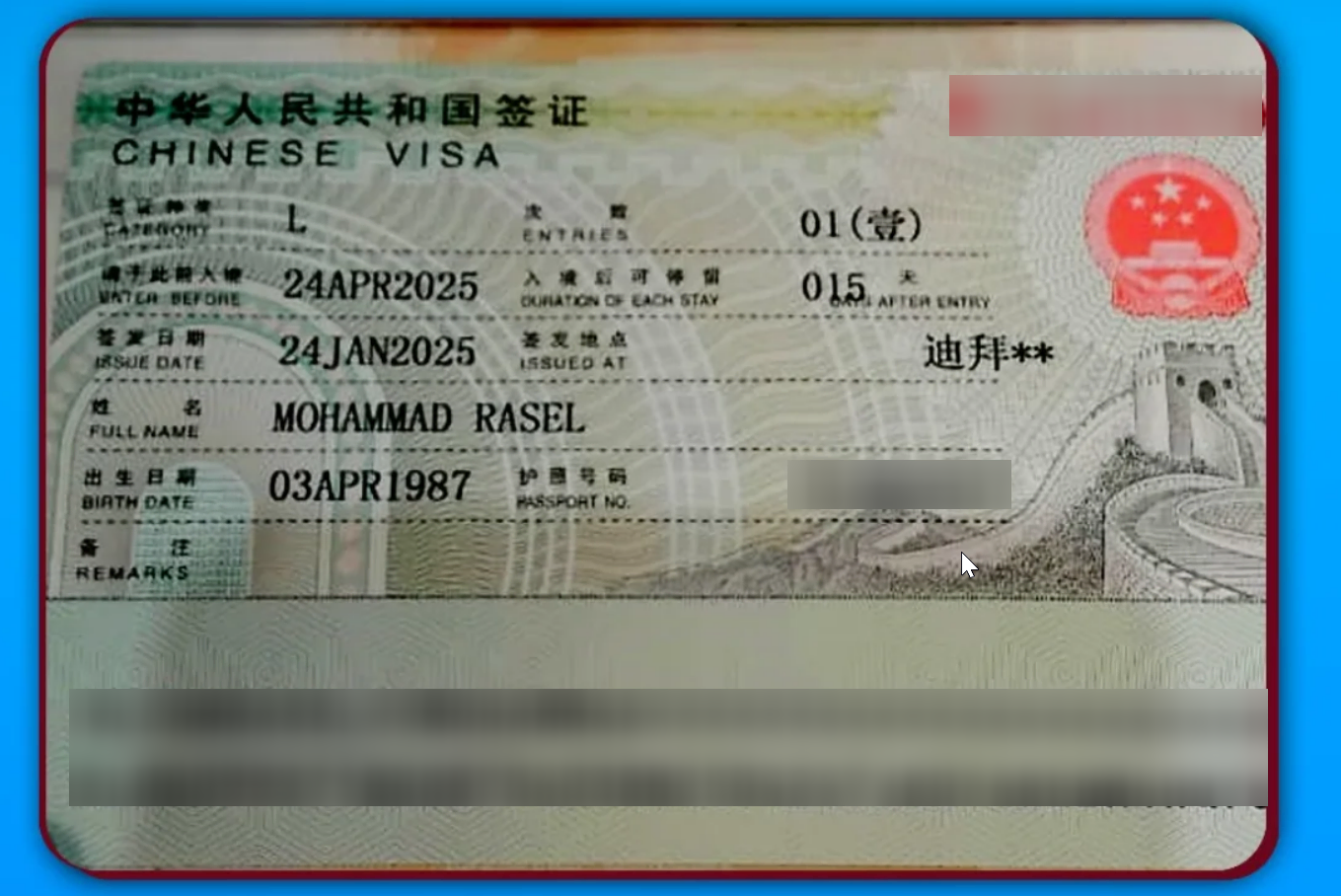

Additionally, manual errors frequently occur in interactions between Arabic and other languages, affecting identity verification. These issues generally stem from differences in language, writing norms, naming cultures, and database compatibility. Immigrants often have to proactively adjust their names to avoid inconveniences.

What Names Do Foreigners Use When They Come to China?

Those who have been online for a long time might recall a famous naming incident in China: Zhao C.

In 1986, Zhao C’s father, wanting to be unconventional, registered his son’s name as “Zhao C.” At the time, name regulations were not as strict, so the name was used for 20 years. However, in 2006, when Zhao C tried to apply for a second-generation ID card, problems arose. China was preparing to draft the Regulations on Name Registration (Draft), which prohibited the use of traditional characters, obsolete variant characters, foreign scripts, Pinyin, Arabic numerals, and other non-Chinese characters in names. After a series of administrative lawsuits, Zhao C won the case but was ultimately forced to change his name.

This incident was one of the most heated topics in Old T’s administrative law class during university. The professor, in particular, was indignant about the case: Zhao C had used this name for 20 years, and the court had supported his right to continue using it. How could a new regulation force him to change it?

Lawtee looked into the current practices for foreigners’ names in China and found that there are essentially two options: using an English name or using both an English and a Chinese name. Languages like Russian, Arabic, Spanish, and Hindi are generally not supported.

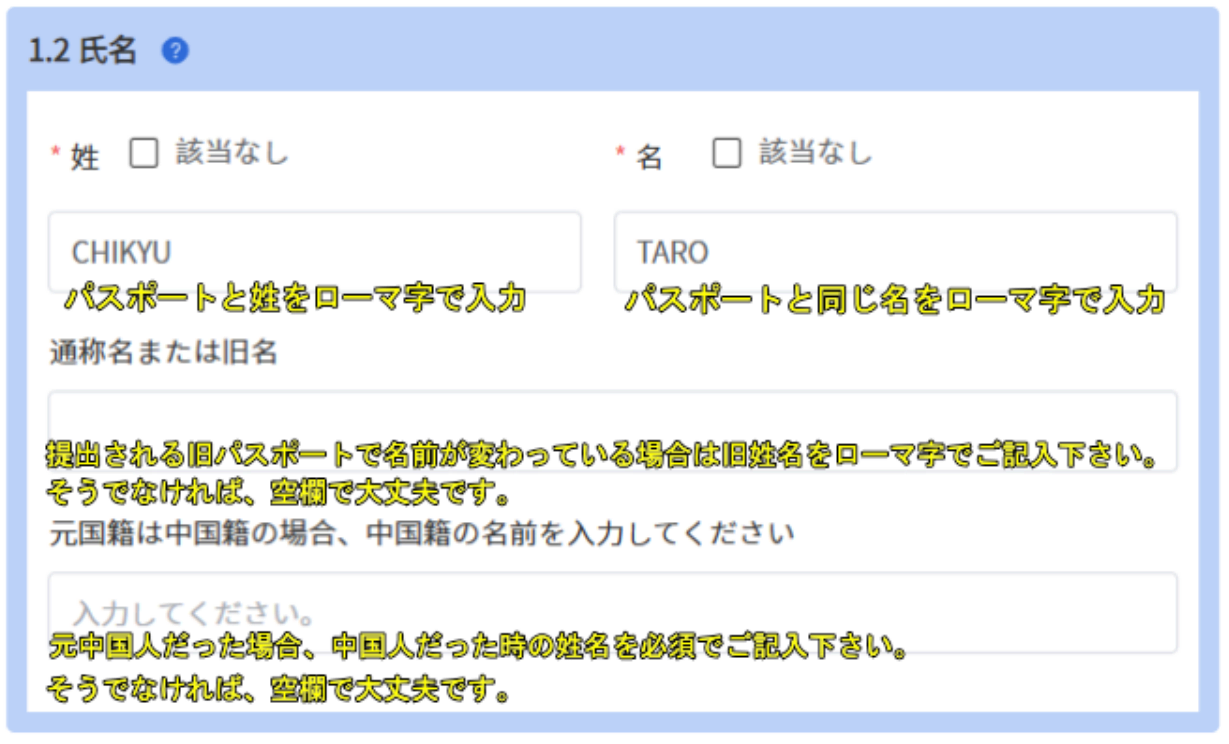

Normally, when foreigners come to China, they primarily use their English names, which are recognizable by systems like banks and railways. For example, the 12306 railway app provides detailed guidelines for name entry, supporting only the 26 letters of the English alphabet.

Foreigners only need to consider adopting a Chinese name if they plan to settle in China or apply for a passport. However, even this is not mandatory; it’s optional. For instance, Lawtee checked the local Public Security Bureau’s Notice on Replacement or Reissuance of Permanent Residence Permits for Foreigners, which states that if an applicant wishes to have a Chinese name printed on their Foreign Permanent Resident ID Card, they must indicate “Document requires printing of Chinese name: XXX” in the “Other Matters to Note” section of the application form. Otherwise, they should write “None.”

In other words, under current circumstances, when a foreigner comes to China, the primary need is to have an English name, while adopting a Chinese name is secondary. As for the issue of choosing an English name, it’s similar to the situations described earlier: foreigners who originally use languages like Russian, Arabic, Spanish, or Hindi will face the same challenges when selecting an English name.

Lawtee believes that as China continues to develop, it will inevitably attract more foreigners to work and even settle here. Many of these foreigners may not be from native English-speaking countries. Instead of having them adopt an English name, it might be more straightforward and appropriate to encourage the direct use of Chinese names, which aligns better with the local context.

After all, neighboring countries like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam have been using Chinese characters for names for thousands of years. Even if the characters differ, corresponding Chinese names can generally be found. Requiring them to provide an English name instead feels somewhat odd.