Does the Glass Dome Design of Huawei's Office Building Constitute Infringement?

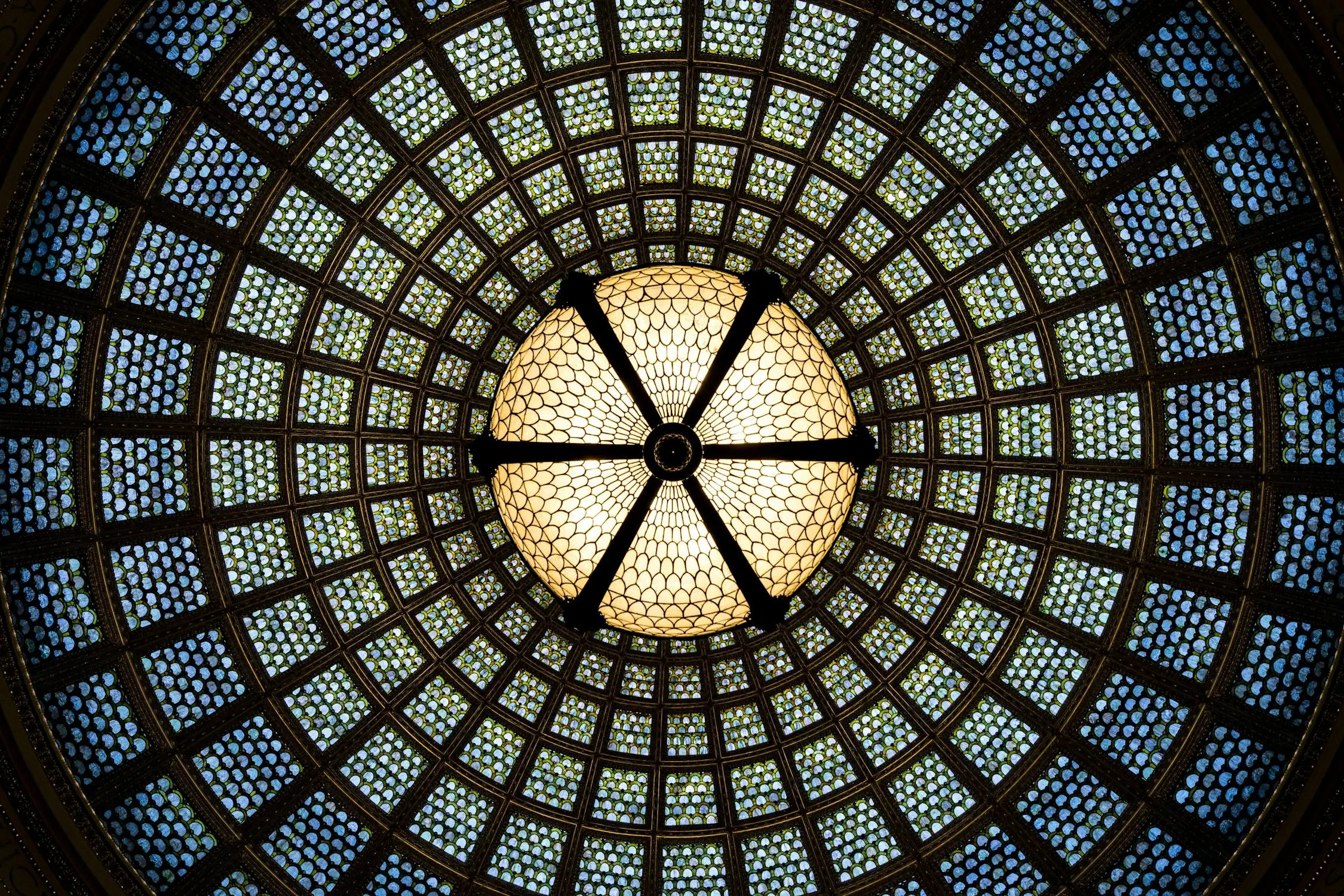

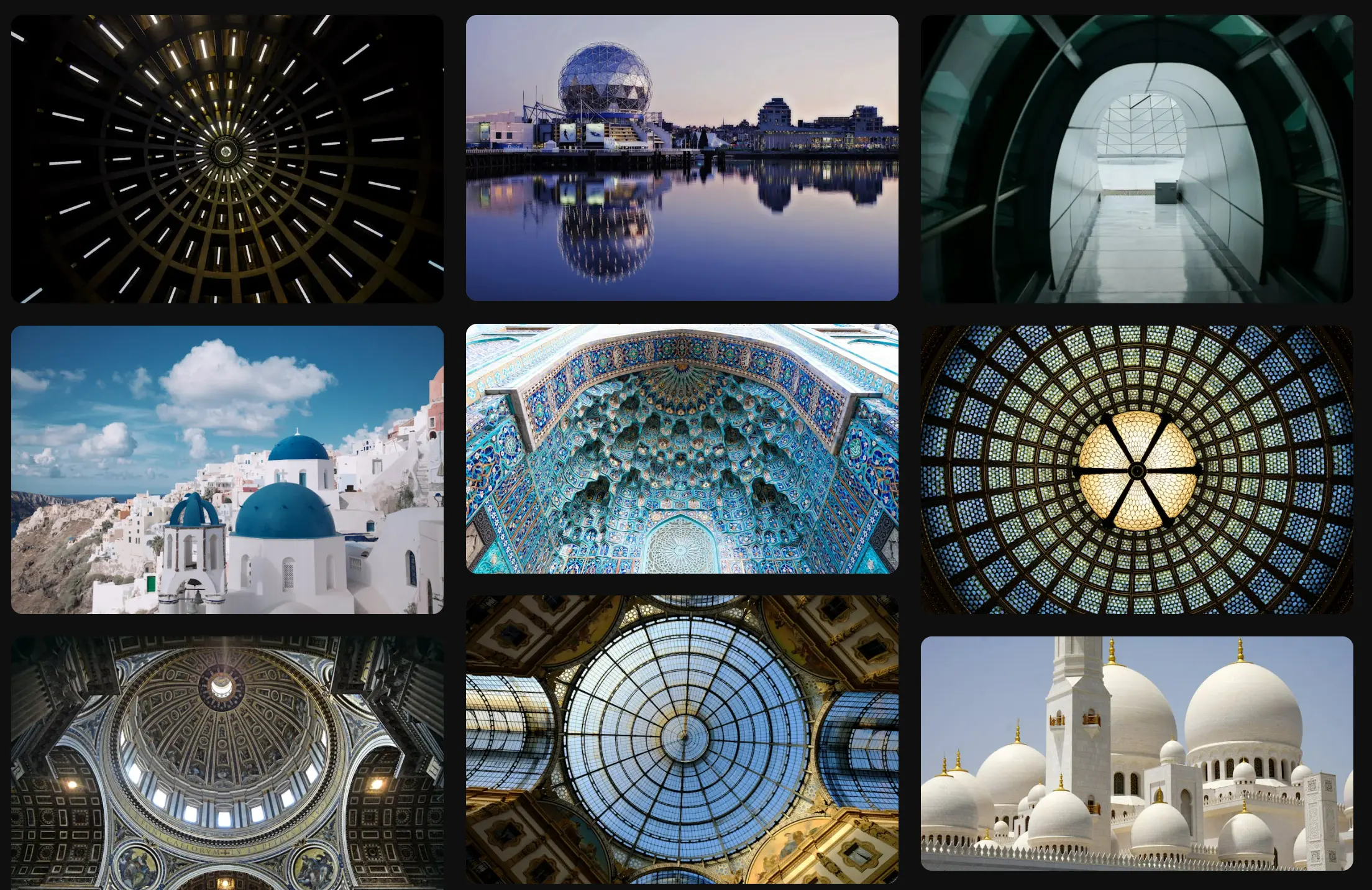

Recently, I came across an article online that, while not exactly news, has resurfaced for discussion . The original article, titled New Huawei Headquarters. Copyright Infringement Dispute , was written by a Canadian art and design company. The main contention is that they believe the glass dome design of Huawei’s office building infringes on their copyright.

Brief Overview of the Incident

In 2018, Canadian designer Victoria Balva was informed by a friend from Asia that a large colored and leaded glass roof in a Huawei office building under construction in Shenzhen bore a striking resemblance to a project she had previously designed. Consequently, Victoria Balva contacted the architectural design firm responsible for Huawei’s office building — Japan’s Nikken Sekkei.

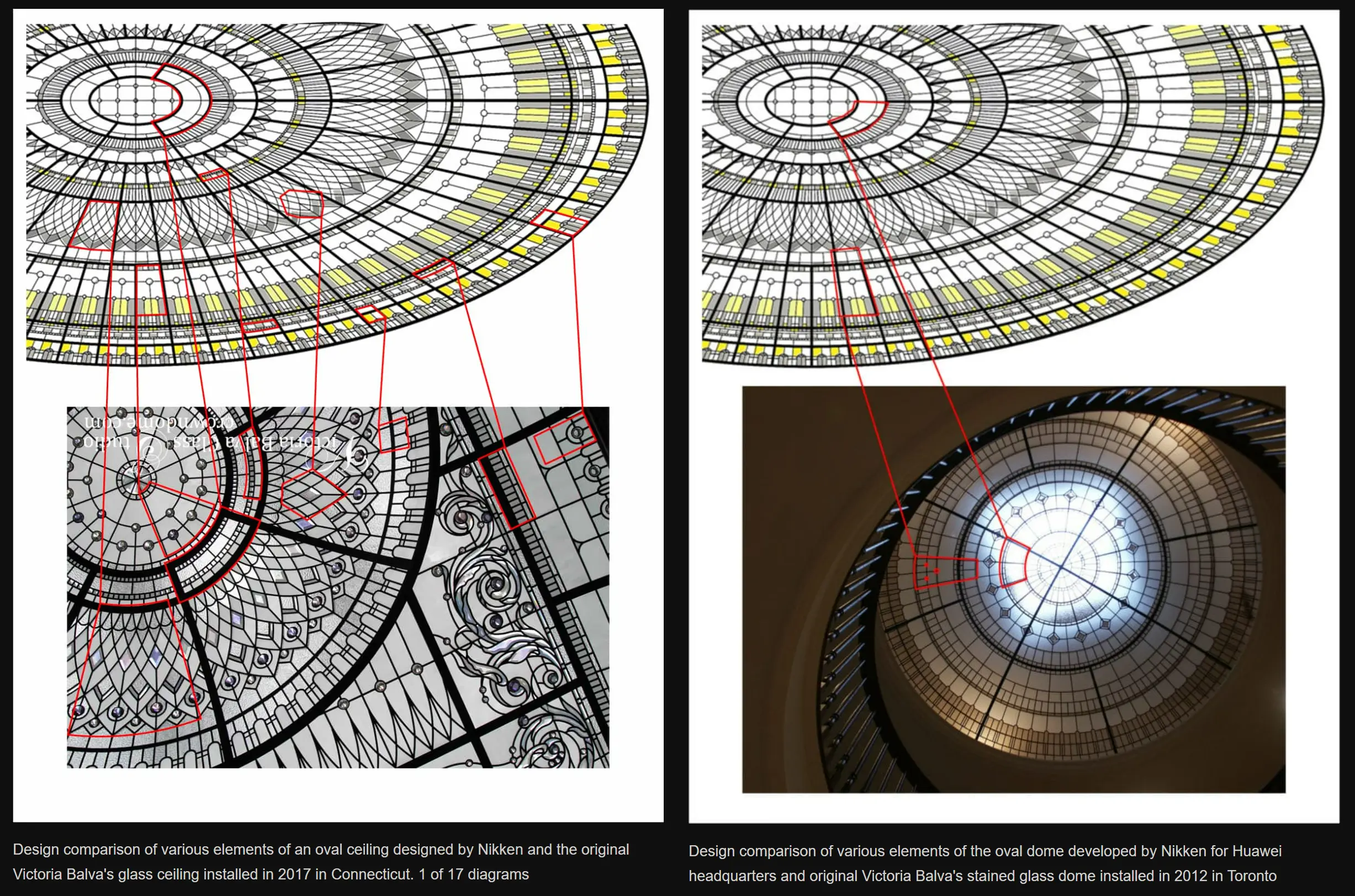

After a brief investigation, Nikken Sekkei admitted that their employees had referenced Victoria Balva’s previous works while designing the building for Huawei. They also enlisted a Canadian lawyer to handle the matter.

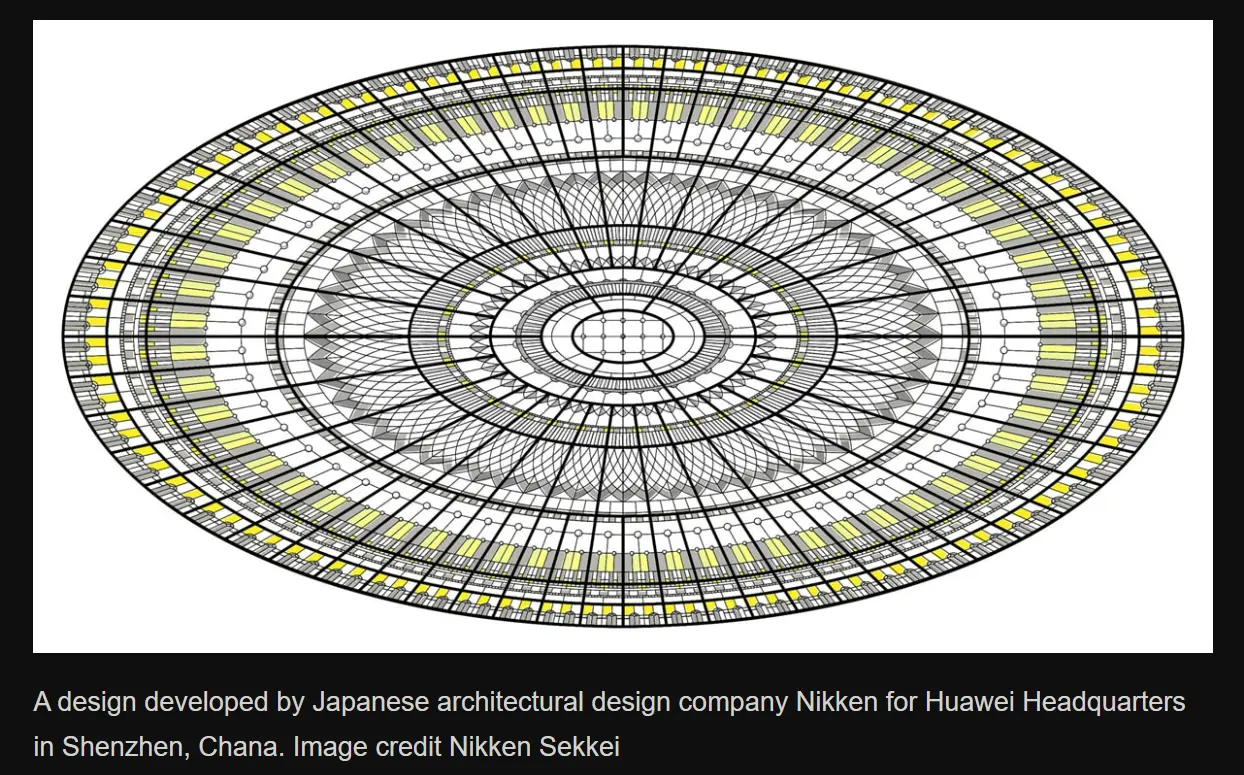

However, after further deliberation, Nikken Sekkei concluded that their design for Huawei was an original work, representing the pinnacle and latest achievement in the decorative glass dome and roof industry. They refused to accept Victoria Balva’s infringement claims.

Given that Victoria Balva’s company is a small to medium-sized enterprise, and considering the legal battle against two large corporations from China and Japan, coupled with differences in intellectual property protection across countries, she realized the case could become quite complex. As a result, she posted the incident on her company’s website.

Initial Impressions on Whether Infringement Occurred

Honestly, my first impression upon seeing the design was that it likely wouldn’t qualify for intellectual property protection. Elements like the mandala patterns in the center of the design could easily be drawn by a child with a ruler. Similar patterns can be found in roof designs, embroidery, tiles, carpets, and even on Chinese currency. As long as it’s not a wholesale copy, it’s unlikely to constitute infringement.

However, intellectual property law isn’t always straightforward, so a detailed analysis is necessary to determine whether the roof design constitutes infringement.

Types of Intellectual Property Involved in the Glass Dome

Common types of intellectual property include copyrights, patents, utility models, and industrial designs. In this case, the glass roof primarily involves copyright and industrial design. Let’s first discuss the industrial design aspect.

Industrial Design

Industrial design refers to the aesthetic aspect of a product, including its shape, pattern, or a combination thereof, as well as the combination of color with shape or pattern, which is new and suitable for industrial application.

Protection for industrial designs is granted based on patent applications. This means that if Victoria Balva and her company did not file a patent application for this roof design, it would be challenging to protect.

Even if an application were filed, it’s uncertain whether such a roof design would be protected in China.

I conducted a brief search in the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Global Design Database using keywords like building dome, glass roof, and roof. The results showed that Canada and the U.S. are more inclined to register such patents, but most of the results were for roof trusses, support systems, panels, and tiles, with no glass roof design patents found (perhaps due to incorrect search methods).

Since the World Intellectual Property Organization under the Hague System considers the specific protection scope of each country when reviewing international patents, it’s simpler to look directly at China’s legal provisions for registering such patents.

According to Chapter 3, Section 7.4 of the 2023 Patent Examination Guidelines, there are 11 types of industrial designs that cannot be granted patents. The relevant provisions for this case are as follows:

(1) Fixed buildings, bridges, etc., that depend on specific geographical conditions and cannot be reproduced.

(3) For products composed of multiple components with specific shapes or patterns, if the components themselves cannot be sold or used separately, they do not qualify for industrial design protection.

(7) Designs that consist solely of geometric shapes and patterns commonly seen in the product’s field.

(10) Partial designs that cannot form relatively independent areas or complete design units on a product.

(11) Partial designs that are merely patterns or combinations of patterns and colors on a product’s surface.

Based on these provisions, industrial design patents primarily protect designs in the industrial application field, typically those that can be reproduced using industrial production methods. A roof design, which is likely a one-off handmade work, may not qualify. Additionally, buildings based on specific geographical conditions cannot be granted industrial design patents, which would need to be considered in relation to the original Canadian building. Furthermore, the alleged copied elements from Nikken Sekkei’s roof design, as highlighted by the Canadian designer, may not be independent enough, as they appear to be small parts taken from multiple roof designs. Moreover, whether these elements are common geometric shapes or patterns in the industry, or merely surface patterns in the overall architectural design, is also debatable.

In summary, under Chinese patent law, proving that Nikken Sekkei’s roof design copied the Canadian designer’s work carries significant legal risks and is unlikely to succeed. If this were to go to court, it would be challenging to pinpoint exactly what was copied.

Copyright

In the realm of copyright, three types of works are relevant to this case: architectural works, engineering design drawings, and artistic works.

- Architectural Works

Architectural works refer to buildings or other structures that embody aesthetic significance. They typically protect the overall appearance, form, and decorative elements of a building. For example, the Beijing Olympic Stadium, known as the “Bird’s Nest,” is a unique architectural work due to its distinctive appearance, form, and external decorations. However, whether a single roof can be protected separately is still a matter of debate. After all, roofs come in limited forms, and if every roof were protected by copyright, humanity might as well return to primitive living conditions.

This issue is somewhat analogous to the protection of car designs. Even though many cars on the market appear similar, in intellectual property law, as long as one of the five main views (front, rear, left, right, and top) of a car differs from another, it is not considered a copy. In reality, most cars borrow elements from various designs, making the boundaries of intellectual property protection quite blurry.

- Engineering Design Drawings

Engineering design drawings face a similar issue. Many architectural projects have designs that look quite similar. For instance, bridges are often built using a few standard designs, with variations mainly in the shape and length of the piers. Similarly, residential buildings often follow similar layouts, such as two elevators serving four apartments per floor, with comparable floor areas. Minor similarities in design are common and do not necessarily constitute infringement. Unless it can be proven that Nikken Sekkei copied the Canadian designer’s drawings entirely, it would be difficult to claim infringement. Based on the existing designs, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of direct copying.

- Artistic Works

Artistic works serve as a catch-all category. If the roof design cannot be protected under architectural works or engineering design drawings, it might fall under artistic works.

However, comparing the Canadian designer’s roof design to Nikken Sekkei’s as artistic works reveals significant differences. Upon close examination, most people would agree that the two designs are not similar enough to constitute copying in an artistic sense. After all, mandala patterns have Buddhist origins and are quite common in China, making it easy to find similar designs.

#huawei #glass dome #copyright #intellectual property #design #architecture