The other night, my child refused to do his weekend homework and even questioned it, saying his teacher told him to “study hard when it’s time to study and play hard when it’s time to play.” But since he hadn’t had enough playtime over the weekend, why should he do homework? I was at a loss. I almost blurted out, “You need to ‘fa dian hen’ (exert some effort) when studying,” but then I thought, he’s only seven years old—maybe such words aren’t necessary yet. Instead, I shared my own experience: when I was little, even light bulbs often didn’t work, so I would light a long bamboo strip for illumination to do my homework, and only by ‘ban man’ (persisting through difficulty) could I finish it.

This conversation got me thinking for days. Those encouraging words my parents and teachers used to motivate us to study when I was young now seem outdated and are gradually disappearing. What exactly is the issue?

Family Expressions

My father often told me, “When studying, you need to ‘hen shen’ (be fiercely determined), to ‘mo hen’ (grind with determination), and to ‘she de si’ (spare no effort).”

I even looked up these three phrases online. The first one, “hen shen,” yielded almost no useful information. Yet, it was a high-frequency term in my hometown—whether for work or study, “hen shen” was essentially synonymous with hard work and diligence. However, I’m not entirely sure if “hen shen” is the correct written form, as in our local dialect, characters like “xiong” (熊), “sheng” (绳), and “xing” (刑) sound similar to “shen” (神).

For the second term, “mo hen,” I didn’t find much useful information either, except in an article analyzing the character Li Mochou from The Return of the Condor Heroes, where the author used “ten years of ‘mo hen’ (grinding hatred), transforming into a demon” to describe her. This aligns perfectly with our usage of “mo hen,” so it’s likely the same term.

The third term, “she de si,” is quite common and means exactly what it says: to spare no effort, even at great cost, to study well.

Overall, in my family and local context, the expressions used were quite “extreme.” Words like “hen” (恨, hatred/determination) and “si” (死, death) are rather blunt, highlighting the “man” (蛮, rugged/unyielding) aspect of rural society.

School Expressions

During my primary and secondary education, teachers also frequently used “hen shen” to urge us to study. “Mo hen” and “she de si” were used less often, perhaps reserved for scolding individual students in the office, as these terms carry a heavier tone.

A significant difference from family usage was that school teachers loved using terms like “fa hen” (exert effort) and “ban man” (persist through difficulty). They often urged students to “fa hen” when studying and reminded them to “ban dian man” (persist a bit) when facing difficult material.

It’s not hard to see that “fa hen” is a relatively common term in modern Chinese, meaning to make a determined effort.

But “ban man” might be less familiar, as it’s a very local,朴素 expression. I did a quick search and found that this term is actually used in many parts of Hunan, quite distinct from the media-popularized “ba man” (霸蛮, stubbornly forceful) that has gained traction in the last couple of decades.

Tracing History

My hometown is in central Hunan, a region rich with historical figures. Within a few kilometers of my home, there are famous ancient and modern personalities such as Jiang Wan, the Chancellor of Shu (though debated), the late Qing dynasty official Zeng Guofan, early important Party leader Cai Hesen, and revolutionary martyr Qiu Jin.

Among them, Zeng Guofan and Cai Hesen left behind abundant written records. So, with a curious mind, I delved into their works for answers.

It didn’t take much effort, as my middle school was named after Zeng Guofan. Every student there had memorized parts of Zeng’s family letters. For instance, this passage was mandatory for all students, as its key concepts were embedded in the school motto: “For scholars studying, the first is to have ambition, the second to have knowledge, and the third to have perseverance. With ambition, one will not be content with mediocrity; with knowledge, one knows that learning is endless and cannot be satisfied with a single achievement; with perseverance, there is nothing that cannot be accomplished. These three are indispensable.” Books like Zeng Guofan’s Family Letters and biographies of Zeng Guofan were not only available in full at home but also in digital formats.

“Man” in Zeng Guofan’s Eyes

I did a simple count: in the Zeng Guofan family letters and diaries I have, the character “man” (蛮) appears 15 times.

As seen in the chart, the vast majority of these “man” characters carry a negative connotation. The most typical example is in a letter Zeng wrote to his son Zeng Jize, where he warns against “man du man ji man wen” (蛮读蛮记蛮温)—what we commonly call “studying mechanically” or “rote learning.”

Jize’s memory for reading is not good, but his comprehension is better. If we force him to memorize every sentence or scold him for not remembering, he will become more and more foolish and still fail to finish the classics. Please ask Brother Zizhi to select 500-600 characters from the classics Jize hasn’t read yet, teach him once and explain once daily. Have him read it ten times; he doesn’t need to memorize it or constantly review it. After he hastily goes through it, he can seek proficiency by reading commentaries later. If he studies, memorizes, and reviews mechanically (man du man ji man wen), he will never achieve lasting proficiency and will only waste time and effort.

Additionally, it’s worth noting that in a letter to his brother Zeng Guoquan, Zeng Guofan offered a very specific critique of their sixth brother Zeng Guohua’s demeanor: “There is a ‘man hen’ (蛮很, rugged and fierce) expression in his face, which most easily intimidates others.”

Brother Wen’s temperament is somewhat similar to mine, but his speech is particularly sharp. Arrogance that belittles others isn’t always expressed through words; sometimes it’s through demeanor, sometimes through facial expressions. Brother Wen’s demeanor has a somewhat heroic air, and his face carries a ‘man hen’ expression, which most easily intimidates others. One must not harbor any sense of superiority in their heart, for what is in the heart manifests on the face.

Undoubtedly, in Zeng Guofan’s eyes, a “man hen” expression was a character flaw requiring vigilance and correction, as it directly reflected one’s inner thoughts.

More importantly, although Zeng never used a term like “ba man” (霸蛮) in his writings, this criticism of Zeng Guohua essentially conveyed the complete meaning of “ba man” and firmly rejected it. The phrase “most easily intimidates others” clearly aligns with the meaning of “ba” (霸, domineering).

This is why, over the years, whenever I hear people say Hunanese like to “ba man,” I can’t help but explain using my hometown’s pronunciation.

After all, even a term like “ban man” (绊蛮) carries a negative connotation in our rural areas. It’s something you might say within the family or among close ones; saying someone else is “ban man” is undoubtedly a negative assessment. As for “ba man,” that’s an even deeper level of criticism.

“Man” in Cai Hesen’s Eyes

I have a copy of The Collected Works of Cai Hesen published in the 1980s. Initially, I couldn’t find a digital version, so I skimmed through it. The book is filled with terms like “savage era, savage countries, savages, savage forces.”

Later, a friend reminded me, and I found a PDF online. After using OCR text recognition and searching, I discovered the character “man” (蛮) appears 98 times in the entire book. 97 of those instances convey the meaning of “savage” (野蛮).

Cai Hesen frequently used “savage” to critique the backward social systems of his time and World War I. His use of “savage” elevated the term from personal cultivation to a critique of social forms and historical stages, much like in Selected Works of Mao Zedong.

There is only one exception. When Cai Hesen first arrived in Paris, while learning French, he described himself using a dictionary to “man kan” (蛮看, read doggedly) newspapers and magazines, “fiercely reading and fiercely translating” a large number of works urgently needed back in China.

On February 2, 1920, Cai Hesen arrived in Paris, France, where he diligently studied French and read Marxist-Leninist works. “Daily, with a dictionary and two pages of newspaper as his routine,” he engaged in “man kan” (dogged reading) of newspapers and magazines. Within four to five months, he collected a large number of pamphlets on Marxism and revolutionary movements in various countries. Selecting the most important and urgent ones, he “fiercely read and fiercely translated,” rendering works like The Communist Manifesto, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, and “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder into Chinese, while studying various schools of socialism and the actual situation of the Russian Revolution.

This “man kan” (dogged reading) and Zeng Guofan’s “man du man ji” (mechanical studying/memorizing) are not identical in meaning, but they are separated by only a thin veil.

Zeng Guofan used “man du man ji” to criticize inefficient study methods that wasted time, while Cai Hesen, under extremely difficult circumstances, treated “man” as a lifeline. Faced with an unfamiliar language and a vast sea of ideological theories, only through this inefficient, “fiercely read and fiercely translated” “man jin” (蛮劲, dogged persistence) could he啃 down and translate大量 new works and ideas, sending them back to aid the revolution.

From Zeng Guofan to Cai Hesen, the character “man” evolved from scolding children for studying “foolishly” to describing a relentless, self-imposed struggle. There is a consistent thread connecting these uses.

Calling someone else “man” is an insult. Telling oneself “yao ban dian man” (need to persist a bit) is motivation and encouragement.

How to View the Term “Ba Man”

As mentioned earlier, “ban man” is indeed used in many parts of Hunan, written variously as “ba man” (巴蛮), “ban man” (扮蛮), or “ban man” (拌蛮). However, I prefer writing it as “绊蛮,” primarily because in our local dialect, the pronunciations of “ba” (巴) and “ban” (拌) are completely different from “ban” (绊). While “ban” (扮) and “ban” (绊) sound slightly similar, “ban” (扮) is pronounced a bit lighter.

That said, some dialect studies prefer using the character “ban” (扮), such as in “ban he” (扮禾, harvesting rice). But undoubtedly, the combination “ban he” doesn’t make much sense etymologically. Perhaps “ban he” (绊禾) is closer, as it involves “tripping” (绊倒) the rice stalks and “bundling them up” (绊成一捆捆).

More importantly, the reason I favor “绊蛮” lies in the dynamic process embedded in the character “绊” (ban): “restraint > obstruction > breaking free.” This恰恰 provides the most precise footnote for the “ban man” spirit.

It points both to the internal困境 Zeng Guofan warned against—being “羁绊” (hindered) by one’s own pedantry or arrogance—and resonates with Cai Hesen’s practice of “man kan” (dogged reading) to “绊” (trip over/topple) barriers of knowledge and the cages of his era.

Tracing its roots, Hunan itself has long been situated within a vast, historical “ban” (绊, entanglement/obstruction) in Chinese history, remaining almost “obscure” before the late Qing dynasty.

It wasn’t until after 1840, with figures like Wei Yuan, Zeng Guofan, and Zuo Zongtang stepping onto the historical stage, that a major转折 occurred.

This obscurity wasn’t due to poverty but rather being “绊” (obstructed) by formidable natural barriers: the Yangtze River to the north, the Wuling Mountains to the south, and the perilous passes connecting to Guizhou and Sichuan to the west. This created a生存状态 that was both封闭自足 and yearning for突破.

It is precisely this geographical “绊” that shaped Hunan’s unique cultural atmosphere and预设 that any individual wanting to venture out and make their mark must first overcome the difficulties Zeng Guofan described as “extremely rugged paths” (路极蛮).

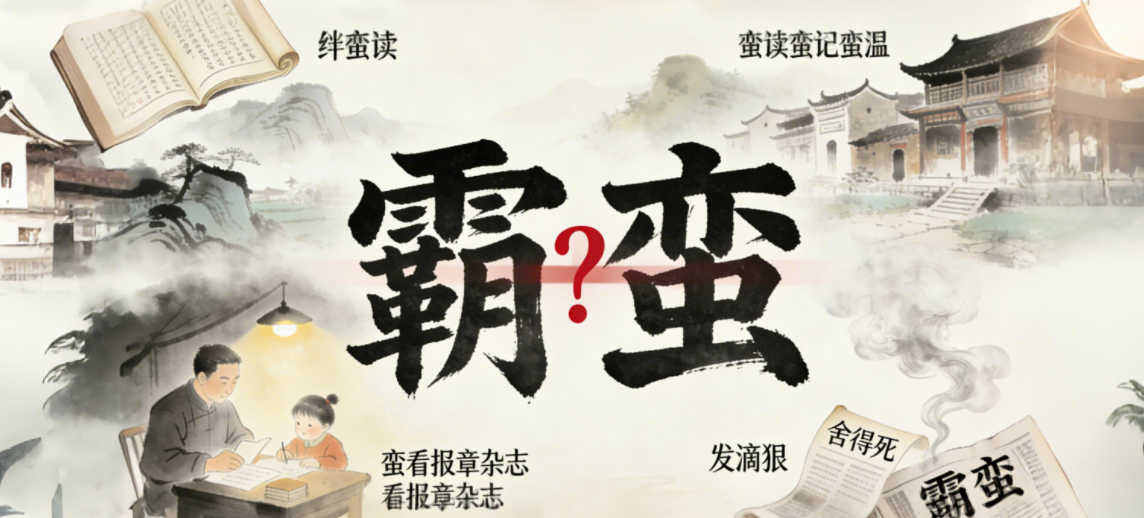

However, “绊蛮” is clearly different from “霸蛮.” The term “霸蛮” likely originated from phonetic transcription errors in works like Zhou Libo’s Great Changes in a Mountain Village, where the heard “ba man” was written as “霸蛮.” It later became solidified through online传播, leading to a semantic shift towards “domineering and unreasonable.”

But undoubtedly, being domineering and unreasonable is绝不是 the original meaning cherished and传承 on this land of Hunan.

The “绊蛮” I追溯 has a spiritual底色恰恰相反.

It is like the bowing-down motion in “绊禾” (harvesting rice). Its core is the反复较量 with the沉重 of life, the憋足一口气 (gathering one’s breath) during prolonged hardship, and the不得不为的韧性 (resilience born from necessity) that emerges from within.

This “绊蛮,“生发于泥土与命运 (born from the soil and fate), is a resilience for survival, not a posture of霸道.

Yet, it is deeply遗憾 that this沉重的内里 (weighty essence) is being消解和遗忘 by countless轻飘的 (frivolous) “霸” characters on the internet.