Astonishing the Autumn Rain

A couple of days ago, during a mock trial session on "Debate and Eloquence," I caught sight of Yu Qiuyu again.

Back in high school, I forced myself to read "Mountain Dwelling Notes," "Bitter Journey Through Culture," and "Boundless Traveler"...

Why did I force myself?

Mainly because my essay writing skills were so poor back then (and honestly, they still are). I had to memorize sentences from these essays to piece together my own writings.

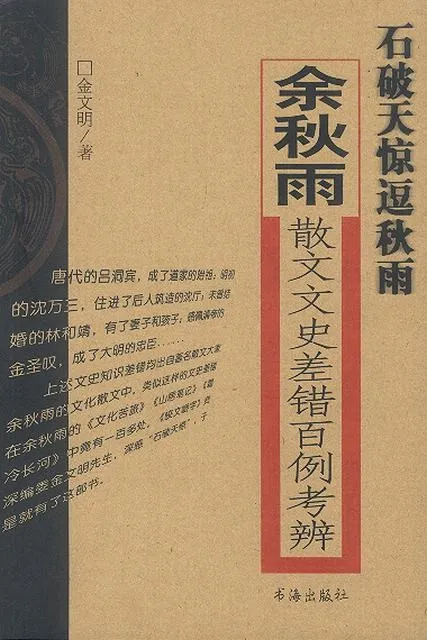

Later, I stumbled upon a book at my cousin's place titled "Astonishing the Autumn Rain," written by Mr. Jin Wenming, the editor of "Word and Phrase." The book meticulously pointed out over 200 historical, cultural, and textual errors in Yu Qiuyu's "Bitter Journey Through Culture" and two other books (or so I recall, the exact number might be off).

The conclusions drawn in this book left my younger self quite disheartened. It made me realize how challenging it is to unify history, prose, and cultural systems.

Since then, influenced by Mr. Jin, I've paid less attention to Yu Qiuyu.

Over the years, I've often seen Yu Qiuyu making appearances everywhere, almost like a TV celebrity.

It feels like he's been sacrificed?

I've generally kept up with books by cultural TV celebrities, delving into new perspectives on the Three Kingdoms, the Analects, and Ming-Qing history.

Especially Mr. Yi's take on the Three Kingdoms—since the two volumes were published over a semester apart, I spent over two semesters flipping through them.

I could mostly memorize them back then, but now, when it comes to Three Kingdoms characters, perhaps only Xun Yu leaves the deepest impression.

As for Yu Dan's interpretations of the Analects, I've always been quite dissatisfied with Confucian thought.

Still, I gritted my teeth and read through it twice, feeling quite uneasy.

Confucius and Mencius misled the nation; Cheng and Zhu even more so!

Sometimes I indulge in a fantasy: what if Emperor Gaozu of Han had chosen the philosophies of Mozi or Han Feizi as the foundation of the state?

Would we have even sent our daughters to the Western Regions?

Yesterday, I skimmed through the Tang Dynasty's "Anti-Classics," which felt quite refreshing, embodying the essence of various schools of thought.

Not confined to Confucianism, it's definitely worth a read. If I had more time, I'd delve deeper into it.

My library card only allows borrowing ten books. Yesterday, I hastily returned nine and brought back a stack of economics books.

After reading many recommendations, it seems that for law students, the most important adjacent disciplines to master are philosophy and economics.

So today, I went and grabbed a pile of philosophy books from the late Middle Ages and early bourgeois period.

Leading the pack is Descartes' "Principles of Philosophy."

I've known for a long time that the critique of "I think, therefore I am" in Chinese political textbooks is utterly misleading.

But back then, I only had a brief introduction to Descartes to base my conclusions on. Now, with this opportunity, I must replenish my knowledge extensively.

Next up are Rousseau's "Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men," Hegel's "Elements of the Philosophy of Right," and Pascal's "Pensées."

There are also works by Voltaire and others.

Although these books are labeled as philosophy or law, especially Descartes' works, they largely cover mathematics, chemistry, and physics—disciplines that later branched off from philosophy. So, I hope they won't be too dull.

I borrowed these books using a friend's library card, so I need to finish them quickly...

The task is quite daunting.

Especially since I also want to use the bilingual version of "Pensées" to prepare for my English proficiency test.

Finally, let's talk about Li He's poem, which I remember was in our high school senior year textbook.

It was an optional text, but since it was within the scope of the college entrance exam, I had to memorize it.

Li Ping's Konghou Prelude by Li He of the Tang Dynasty

Wu silk and Shu wood stretch high in autumn,

Empty mountains, still clouds, stagnant and unmoving.

Jiang'e weeps over bamboo, the plain maiden grieves,

Li Ping of China plays the konghou.

Jade shatters on Kunlun, the phoenix cries,

Lotus weeps dew, orchids smile.

Twelve gates melt cold light,

Twenty-three strings stir the Purple Emperor.

At the place where Nüwa mended the sky with stones,

Stones break, heaven startles, teasing autumn rain.

Dreaming, she enters the divine mountains to teach the divine old woman,

Old fish leap waves, thin dragons dance.

Wu Zhi, sleepless, leans on the cassia tree,

Dewy feet slant, wetting the cold hare.